57 Squadron - 1916-1918 - World War I

Following its formation in June 1916, 57 Squadron crossed to France in December of that year flying the FE2d in the fighter-reconnaissance role. In May 1917, the Squadron re-equipped with the DH4, moved to the Ypres sector and began long-distance reconnaissance, bombing and photography missions. While based in France, the Squadron destroyed 166 enemy aircraft and dropped 285 tons of bombs. It also exposed 22,030 photographic plates and completed 96 successful reconnaissance runs.

France

Leaving Copanthorpe in December 1916, the Squadron deployed to France as a fighter reconnaissance unit equipped with the Royal Aircraft Factory FE2d, a single-engined two-seat ‘pusher’ biplane.

A 57 Squadron FE2d

The aircraft had played a pivotal role in ending the Fokker Scourge which had led to German air superiority over the Western Front from summer 1915 to the spring of 1916. But by April 1917, the aircraft was withdrawn from offensive patrols as they were outperformed by the new German Albatross D I and Halberstadt D II aircraft.

An Interesting Great War Photo with 57 Squadron Connections: 107th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, “A” Company Subalterns, Lens, France, 29 July 1917

by John Moses, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

It is worth noting on this postcard dated 29 July 1917, the correspondent identifies two of the officers as Indigenous North American Indians (“First Nations”, in current Canadian usage) from Canada. Number 1 is Lieutenant Oliver Milton Martin, Mohawk, from Ohsweken, the village centre of the Six Nations of the Grand River Indian Reserve near Brantford, Ontario. Number 6 is the correspondent himself (and my great uncle), Lieutenant James David Moses, from Smooth Town, the Delaware district on the same reserve.

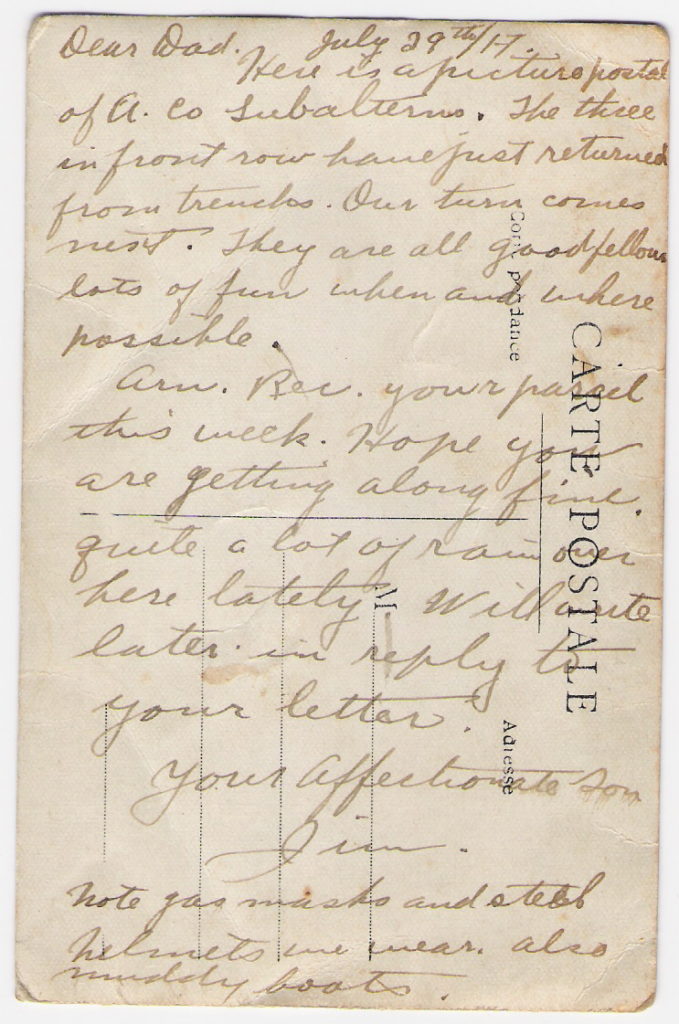

July 29th 1917

Dear Dad

Here is a picture postal of [A Co] subalterns. The three in front row have just returned from trenches. Our turn comes next. They are all good fellows, lots of fun when and where possible. [Have received] your parcel this week. Hope you are getting along fine…quite a lot of rain here lately. Will write later in reply to your letter. Your affectionate son, Jim

Note gas mask and steel helmets we wear also muddy boots

107th Battalion ‘A’ Company Subalterns

1 Lieutenant O M Martin [Ohs] ‘Mohawk’

2 Lieutenant [A L Cavanaugh] Winnipeg ‘Irish’

3 Lieutenant H Dawson Montreal ‘Scotch’

4 Lieutenant [F Biley] Kamloops ‘Irish’

5 Lieutenant [S V Smith] Winnipeg ‘English’

6 Lieutenant J D Moses Smoothtown ‘Delaware’

Moses was writing home to his father, Nelson Moses, in the days preceding the rotation of the 107th Battalion, Canadian Expedtionary Force (CEF) into the lines north of Lens, for what would transpire as the heavy fighting for Hill 70. After Vimy Ridge in April 1917, the fighting north of Lens during August 1917, was perhaps the pre-eminent Canadian engagement of the entire First World War.

The photo documents one of Canada’s largely Indigenous formations of the Great War. Originally recruited around Winnipeg, Manitoba, the 107th Battalion was augmented on arrival in France with selected members of the recently disbanded 114th Battalion, CEF, “Brock’s Rangers”. The 114th had been recruited in and around the Six Nations Reserve, and into which unit both Martin and Moses had originally been attested.

Like the 114th, approximately half of the 107th’s 800 man strength, was comprised of First Nations and Metis troops from across the Canadian provinces of Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec. The photo is an interesting commentary on the rising sense of Canadian nationalism and identity that unfolded during the course of the War. In writing home, Moses found it worth noting the ethnicity of his brother officers: one could claim “Canada” as their country, while still claiming “Delaware” or “Mohawk” (or “Scotch” or “Irish” or “English”) as their nation.

Subsequently posted for flight training with the Royal Flying Corps in September 1917, Lieutenants Moses and Martin were among only three Canadian Indians who would hold commissions in the British flying services during the Great War.

The third was John Randolph Stacey, a Mohawk from Kahnawake near Montreal, Quebec, who qualified as an RAF pilot, but who was killed in a flying accident in England on 8 April 1918. Just a week before Lieutenant Moses had been reported missing on 1 April 1918 while serving on 57 Squadron as an aerial observer and air gunner.

Martin survived the War as a pilot and remained active in the Canadian militia during the inter-War years. He was recalled to active service during the Second World War, as brigadier in charge of infantry training of Canada’s west coast. Martin’s appointment as brigadier remains the highest rank yet attained by an Indigenous person in the ranks of the Canadian Armed Forces.

Lieutenant Moses and his pilot, 2nd Lieutenant Douglas Trollip (a South African) were reported missing by the RAF on 1 April 1918 - the day on which the former RNAS and RFC amalgamated to create the RAF proper. The destruction of their DH4 aircraft (serial no. A7872) was attributed by the German Army Air Force to one Leutnant Hans Joachim Wolff. Wolff was a member of Jagdgeschwader von Richtofen, more commonly known in English as the Red Baron’s Flying Circus.

These particular facts notwithstanding, the training Moses received as an observer and air gunner was typical for an aspiring aviator from the Canadian dominion during the Great War.

Lieutenant James Moses

Moses had previously served as an infantry officer with the 37th Haldimand Rifles of Canadian Militia, and with the 114th and 107th Battalions of the CEF, from the date of his enlistment on 19 November 1915, until he was seconded to the RFC. Moses was in action with his battalion as an infantry officer at various locations across the Somme and on the Ypres Salient from the time of the 107th’s arrival on the continent in February 1917, and he was present at the heavy fighting for Hill 70 near Lens from 15 – 25 August 1917.

On 3 September 1917 he was transferred for duty as an Army Observer with the Royal Flying Corps. He began flight training with 98 Squadron as an air gunner and artillery observer in England on 19 September 1917; and on 3 January 1918 he returned to France where on 8 January he was attached for duty with 57 Squadron RFC, based then at St. Marie Cappel and later, Boisdinghem near St. Omer.

57 Squadron at this stage of the War was a reconnaissance and bombing squadron equipped with De Havilland DH4 two-seater aircraft, and as events transpired, it would soon be heavily involved in air operations and ground support missions aimed at countering the great German Spring Offensive of March 1918. From 21 January through 31 March 1918. Moses, as an artillery observer and air gunner, successfully completed a total of thirteen bombing raids and seventeen photographic, artillery spotting, and related reconnaissance flights.

An Airco DH4 of 57 Squadron

James Moses in peacetime had been a teacher in a one-room schoolhouse on the Six Nations reserve. The cumulative effects of his months of war service both as an infantry officer and subsequently as an air gunner and observer, are apparent in the graphic quality of the letters he wrote home to his father. One extract will suffice, from what would prove to be his final letter home:

France, 30 March 30 1918

Dear Dad …Just a few lines to let you know that I am getting along O.K … My pilot and I have had some very thrilling experiences just lately. We bombed the German troops from a very low height and had the pleasure of shooting hundreds of rounds into dense masses of them with my machine gun. They simply scattered and tumbled in all directions. Needless to say we got it pretty hot and when we got back to the aerodrome found that our machine was pretty well shot up.

On 1 April 1918, the day on which the former RNAS and RFC were amalgamated to create the Royal Air Force, Moses and Trollip were reported “Missing” near Bapaume, France, during their fourteenth daylight bombing run together. Lieutenant Moses’ father received the following telegram dated 5 April 1918:

Sir

I am commanded by the Air Council to confirm a telegram from this office to notify you that Lt. J.D. Moses of the Royal Air Force is missing. I am to point out this does not necessarily mean that he is killed or wounded and to say that you shall be immediately informed as soon as any definite news is received. Should you receive any further information from any source I am to request that you will communicate immediately with this office.

Nelson Moses, father of Lieutenant Moses, wrote a moving poem entitled The Missing Airman upon receiving word of the fate of his son. The poem was subsequently published in a local newspaper, likely the Brantford Expositor. An obituary concerning the fate of Lieutenant John Randolph Stacey, the other First Nations casualty of the RAF, appeared in the Toronto Evening Telegram on 12 April 1918 (one week following notification of the loss of James Moses) under the following headline:

Killed While Flying ~ Lieut. John R. Stacey, A Young Iroquois Officer Meets His Death ~ Lieut. John Randolph Stacey, one of the four Iroquois officers who went overseas in Brock’s Rangers, has met his death through an airplane accident.

The names of Lieutenant James David Moses, aged 28, and 2nd Lieutenant Douglas Price Trollip, aged 23, are duly inscribed on the Monument to the Missing of the Air Services at Arras. The German Air Force records referred to previously indicate their aircraft was brought down near Grevillers. It is possible their graves are amongst those marked “Known unto God” in Grevillers British Military Cemetery, which I have visited on pilgrimage, as well as the Monument at Arras.

Monument to the Missing of the Air Services, Arras

The Moses family today on the Six Nations Reserve retains in its possession a set of original correspondence and related documents and photographs shedding light on the war service record and brief First World War flying career of Lieutenant. Moses. The letters, photographs and telegrams comprising this record are of interest on a number of levels.

Technically, they provide insight into RFC/RAF photo reconnaissance work, artillery spotting, ground support, and day bombing operations on the Western Front at the height of the final great German offensive of the War; and they provide enthralling detail into the genesis of close air support and ground attack by air power operating in support of infantry.

Politically, they shed light on the Great War military service of one Native Canadian in the forces of the British Empire, recalling an alliance between the British Crown and the Six Nations Confederacy of Iroquois and allied Indian nations that originated in the 18th century (known as the “Covenant Chain”, symbolic of trading and economic partnerships in peace, and military alliance in war).

Finally, on a humanitarian level, they testify to some of the last recorded thoughts and feelings of a young aviator engaged in the hazardous duty of flying operations over the Western Front in the final year of the First World War.

In total, more than three hundred men from the Six Nations of the Grand River volunteered for duty with the Canadian Expeditionary Force or other armed services of the British Empire during the Great War. Two hundred and ninety-two finally shipped overseas. Of these, thirty-eight, including James Moses, failed to return.

One female Six Nations resident, Edith Anderson Monture (my maternal grandmother), served as a nurse with the U.S. Army Nurse Corps of the American Expeditionary Force. Across Canada, more than four thousand First Nations citizens volunteered for service during the Great War, notwithstanding that their legal status and later treaties with the dominion of Canada exempted them from any such obligation.

57 Squadron today may recall with just pride its Great War origins as a diverse force, reflective of the diversity of the Commonwealth and Empire.

Christmas 1917

After a year in France, life somehow began to establish a routine - if that can be imagined - with a social programme. The photo below shows the programme for the Xmas 1917 Squadron Review.

After just six months deployed in France, the Squadron re-equipped with the 2-seat Airco DH4 aircraft, designed by Geoffrey de Havilland. Powered by a single Rolls-Royce Eagle engine, the DH4 was the first British 2-seat light bomber to be equipped with effective defensive armament. The pilot had a .303 Vickers machine gun, and the observer a .303 Lewis machine gun, and the aircraft could carry two 220 pound or four 112 pound bombs.

A De Havilland 4 of 57 Squadron, 1917

By the end of 1917, 57 Squadron was based at Boisdinghem in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais conducting long-distance reconnaissance, bombing and photography missions.