More on DX-P

I am indebted to my good friend Dirk de Quick of the Wings of Memory group for sharing the following information about the crew of DX-P. I have tried to present the information in a chronological order where possible. No doubt new information will be unearthed in the years to come which will fill in some of the gaps.

For me, the story begins on 29 September 2012, when I had attended a ceremony to commemorate the crew of Lancaster W4234 DX-P of 57 Squadron. The aircraft was shot down by German night fighters on 21 December 1942 over Belgium. As is so often the case, the story of crash and, in particular, of the crew members was at that time only partially known. Since then, more pieces of the story have emerged and new mysteries have unfolded.

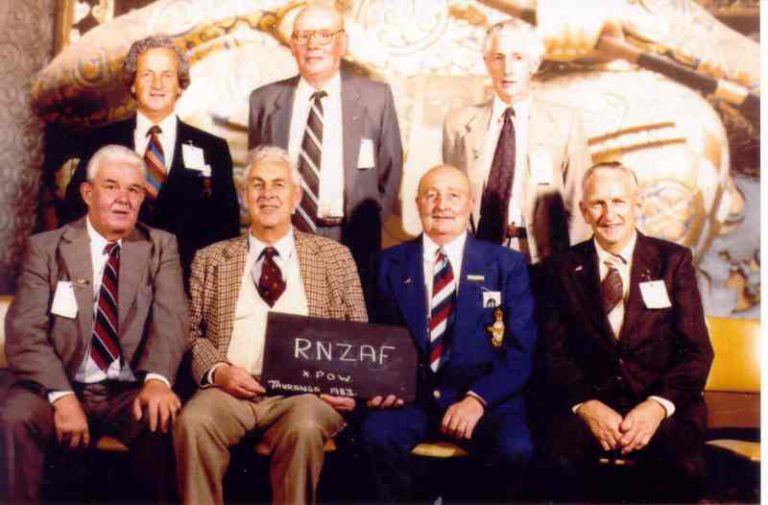

The Crew of DX-P, 57 Squadron 1942. (Sergeant John Drain is believed to have taken the photo)

During the ceremony in Lierde, I stated that crewman Sergeant John Drain had been the rear gunner. However, after reading a copy of my speech, Sergeant Roden Pickford’s son, Jeff Pickford in New Zealand, was quick to put me right. He noted that his father had always flown as rear gunner when flying with Pilot Officer Bowles. Embarrassed to have got this wrong, I asked our Information Officer, Allen Hudson, if he could confirm the truth. Allen said that it was not unheard of for rear gunners and mid-upper gunners to change places which might have led to the confusion:

"Have double checked Loss Register and Sgt Pickford is definitely listed as flying as mid-upper gunner in W4234. However the ORB (Operational Record Book) prepared by the Squadron, would have been copied from the crew Battle Order for that operation. It was not unknown for the two gunners to swap position. So Pickford could have been in the rear turret.

It must be borne in mind that the rear gunners parachute was not held in the rear turret - there was no room. The RG's chute was clipped into a chute holder in the rear part of the fuselage (starboard side) next to the rear door. This required the rear gunner to vacate his turret into the fuselage before he could clip it to his harness. The mid-uppers chute was in a similar holder on the fuselage starboard side near to his turret. With the rear door clipped open both gunners would have had a good chance of baling out.

In our crew the bail out drill was for both gunners, the WOp/AG and the flight engineer to use the rear door. The Nav, Bomb Aimer and Pilot went out of the front exit on the floor of the fuselage. In early 1945 a flat pack back parachute was issued to rear gunners. The theory was they could turn their turret through 90 degrees, use the "dead mans" handle, force open the turret doors and bail out backwards. This didn't always work as the ammunition servo unit restricted getting ones legs out. We of course wore the heavy suede flying boots which were very restrictive in movement in the turret."

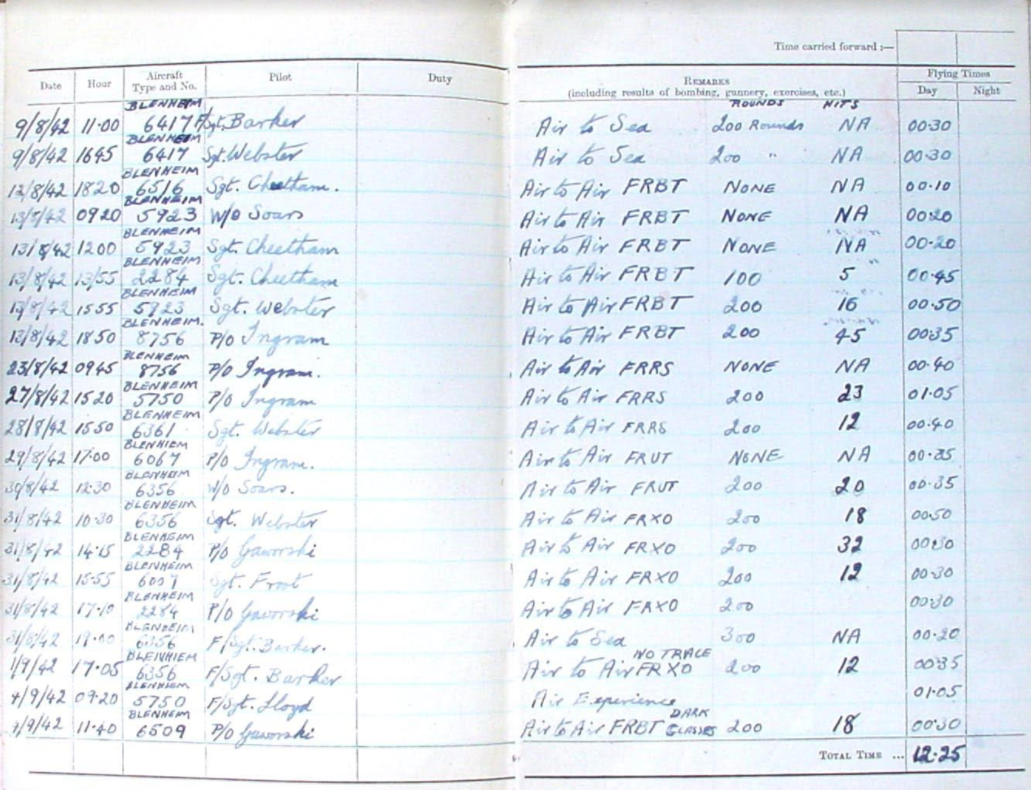

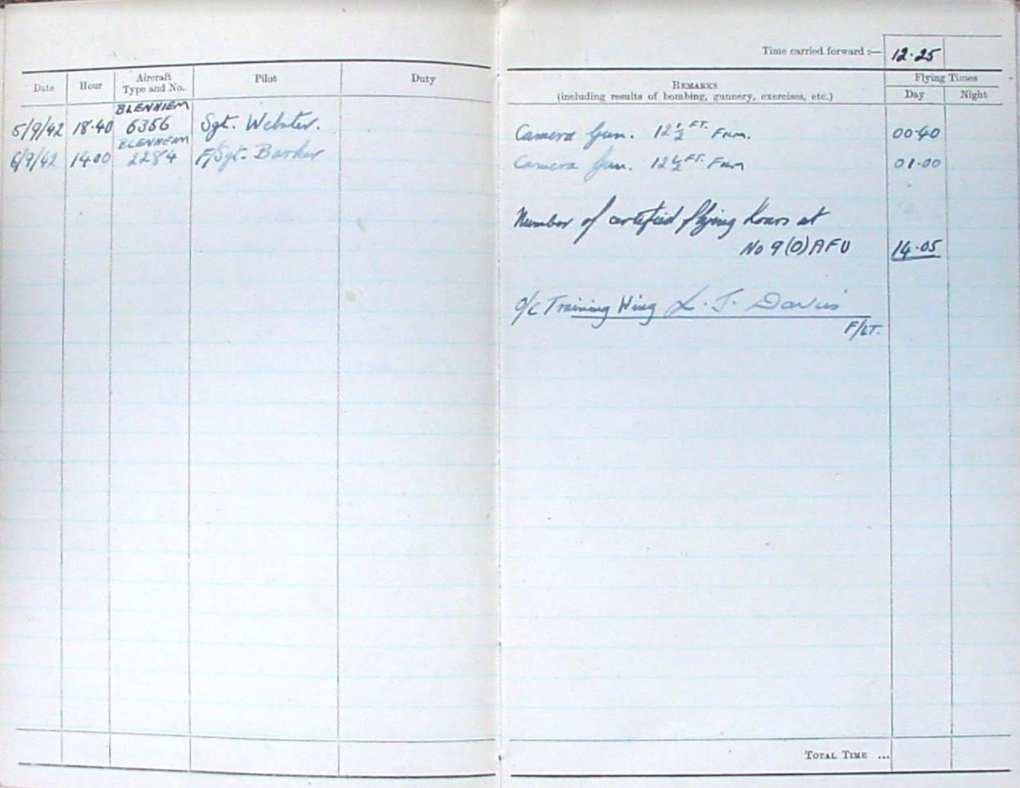

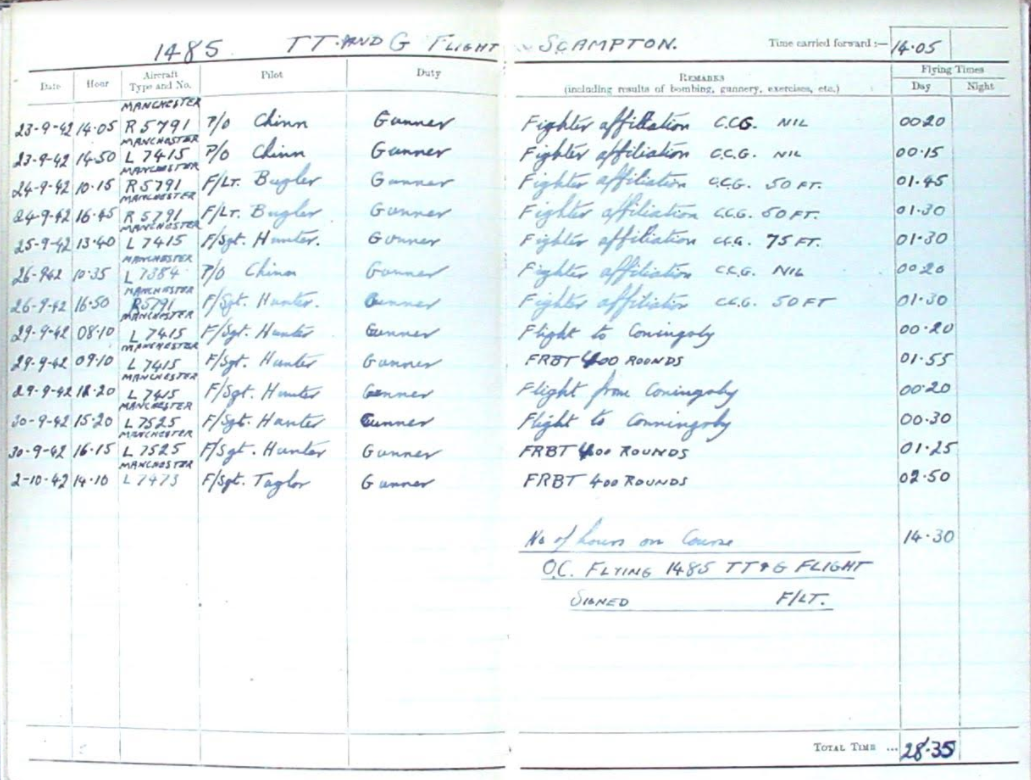

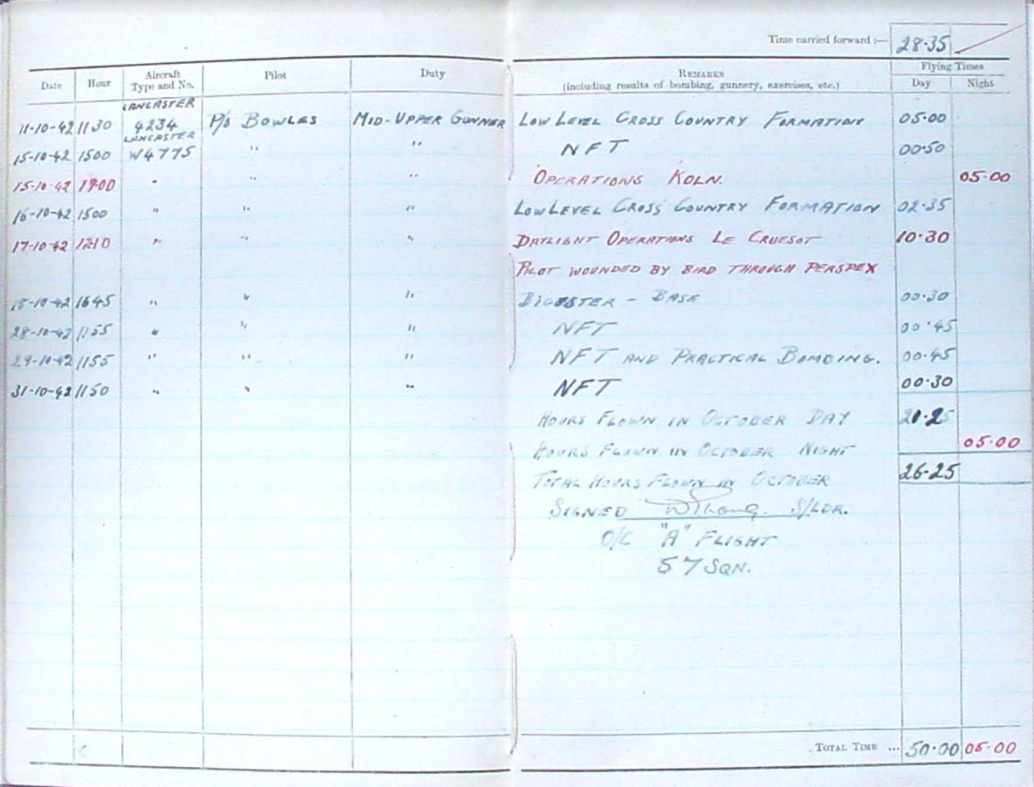

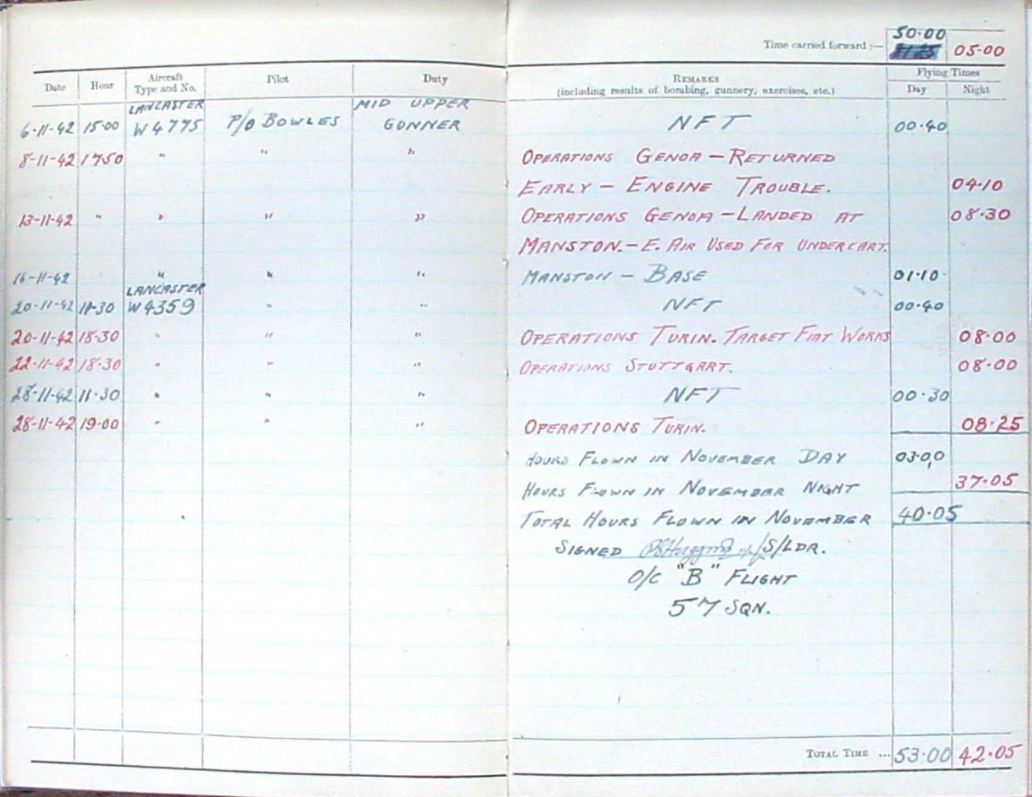

It transpired that the family had always referred to John Drain as a tailgunner. It also emerged that as Roden Pickford was taller than John Drain, they may have swapped positions. This despite both Drain’s and Pickford’s logbooks stating that they were mid-upper and tail gunners respectively. In October 2012, Jeff Pickford shared copies of his father’s logbook:

Roden Pickford's flying logbook - 21 December 1942 'Ops Munich - A/c failed to return'

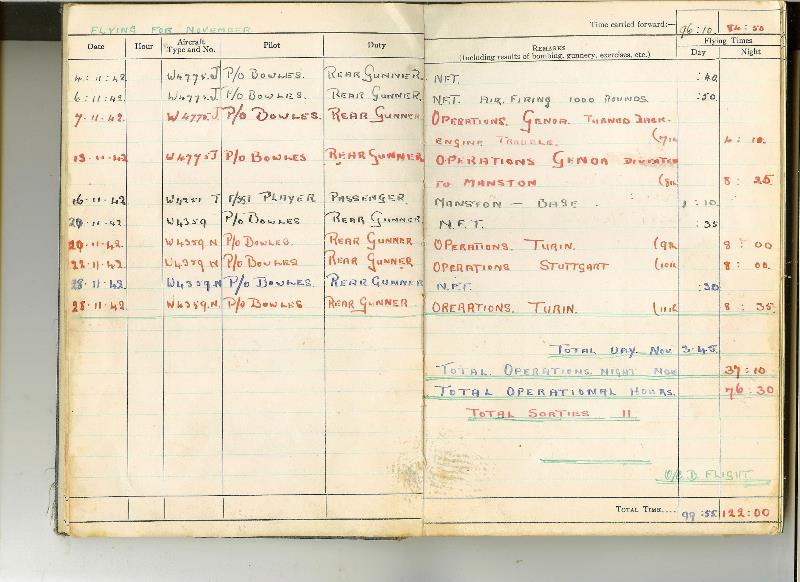

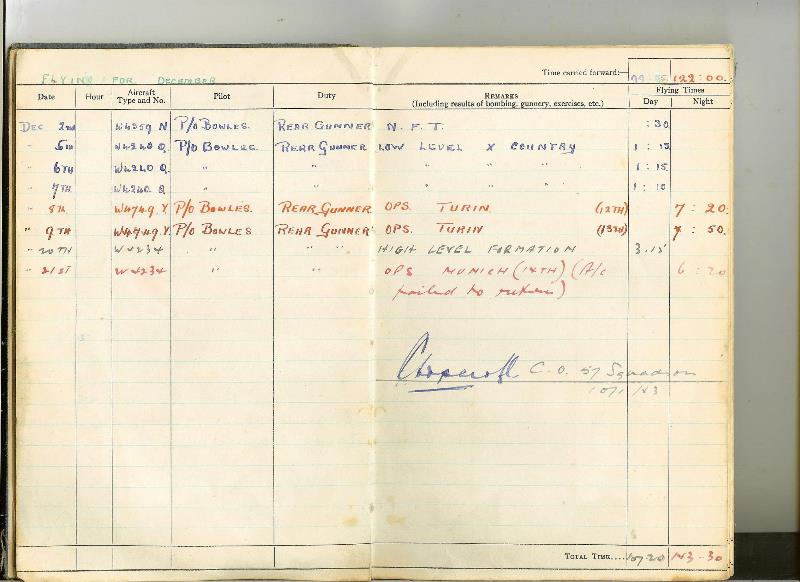

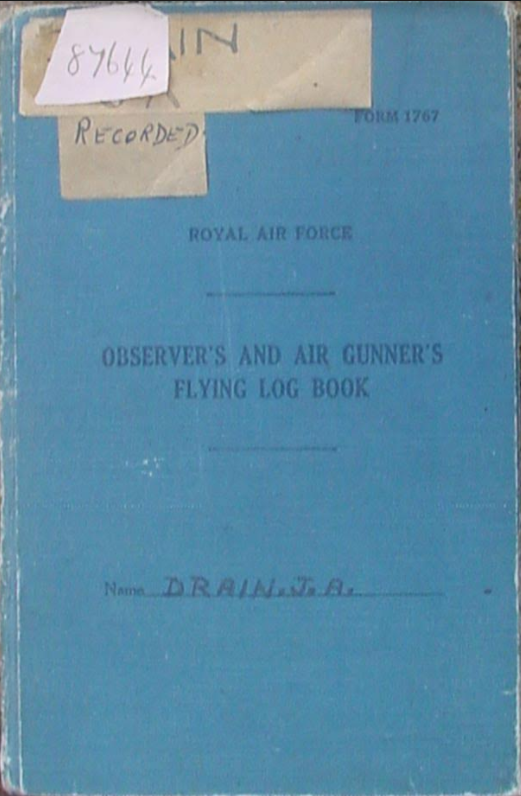

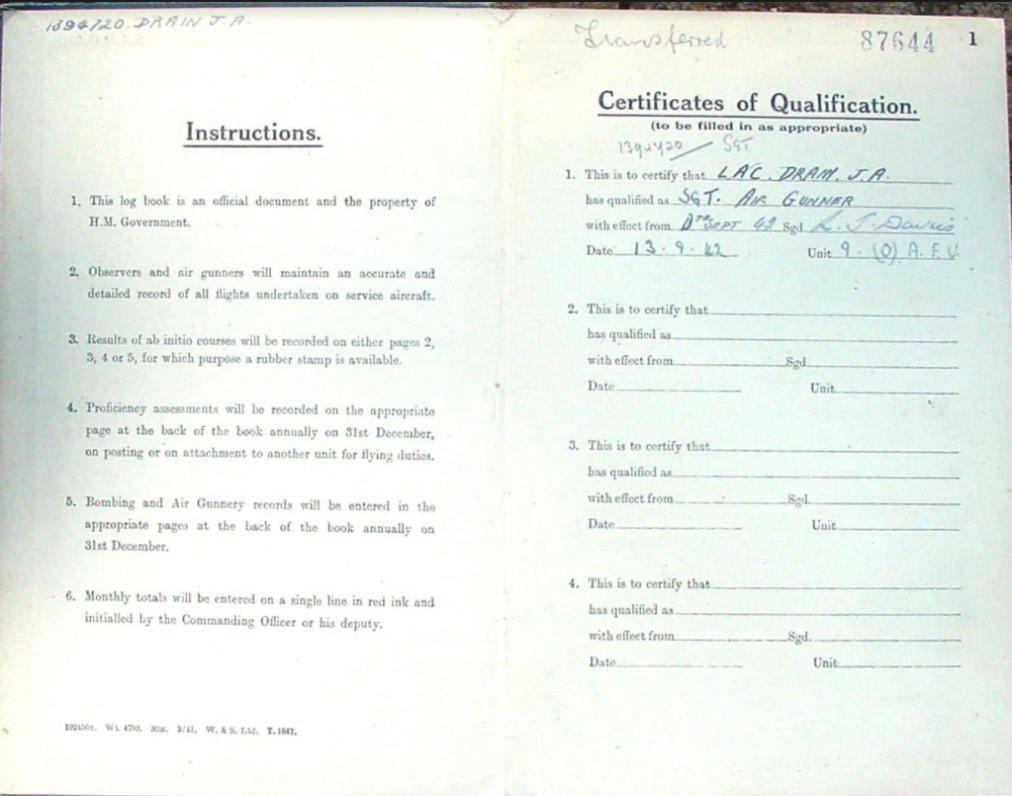

In November 2013, a copy of John Drain’s logbook confirmed that he occupied the mid-upper gunner position on DX-P on that fateful night.

Sergeant John Drain, Mid-Upper Gunner DX-P

Just scanning John Drain’s logbook reveals some remarkable facts. Leading Aircraftman Drain qualified as a Sergeant Air Gunner on 13 September 1942. He had the grand total of 14 hours and 5 minutes under his belt flying on the Blenheim. This was followed by 14 hours and 30 minutes flying the Manchester. His first sortie on the Lancaster was on 6 November 1942 as he started his first operational tour. His first first mission – to Turin – just 2 days later, was unsuccessful as the crew had to return early with engine trouble. On 13 November 1942, the crew completed their mission targeting Genoa.

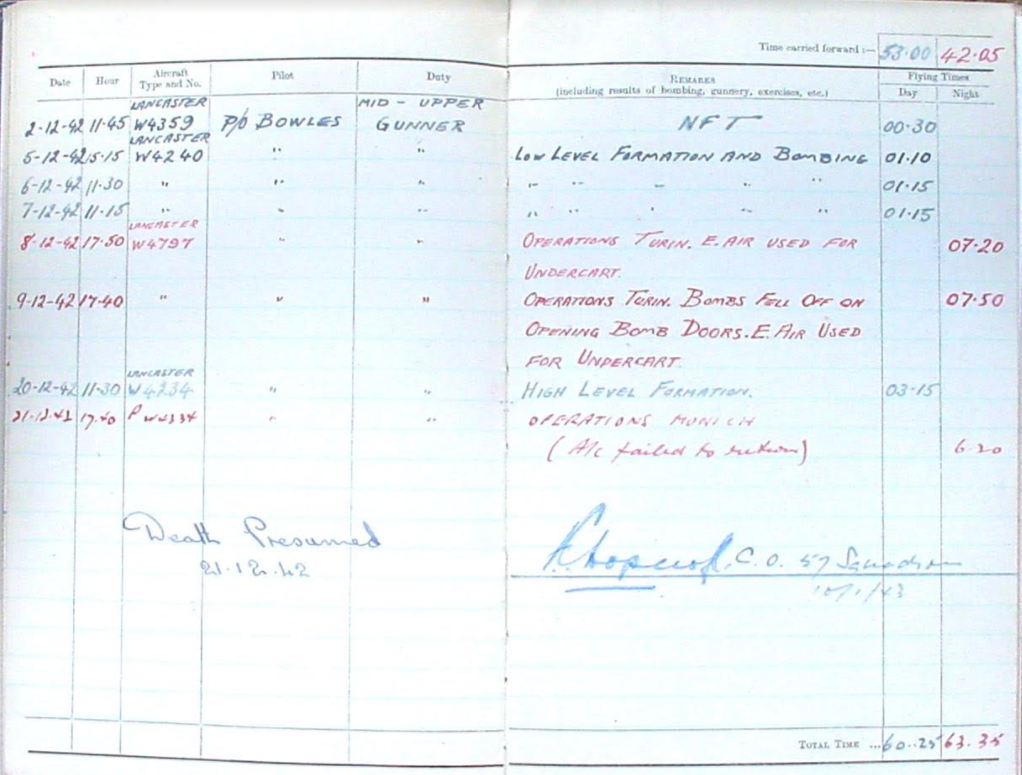

A drawing made by Pilot Officer A Pollen to mark the mission to Genoa on 13/14 November 1942 by the crew of DX-P. Seven weeks later the crew was to crash near Lierde, Belgium.

On 9 December 1942, Drain notes that the bombs fell off when opening the bomb doors on a mission to Turin. Less than 2 weeks later on 21 December 1942, the crew failed to return having crashed in Belgium on a mission to Munich. Drain had amassed just 124 flying hours in his RAF career.

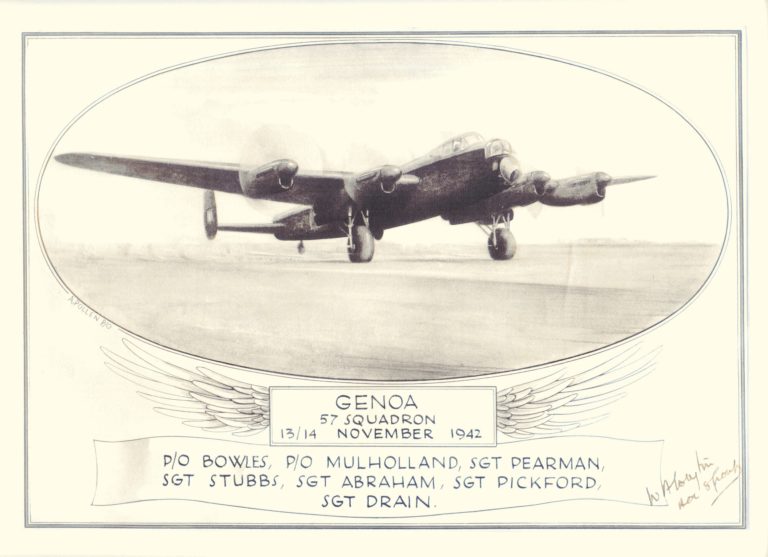

Roden Pickford was the only crewmember to survive the loss of DX-P, but was taken prisoner. Here he is pictured with fellow RNZAP PoWs in Tauranga, New Zealand in 1983. He died in 1986.

Back to the 2012 ceremony in Belgium and information from Sheila Sinclair (a 2nd cousin) writing to Wing of Memory about Eric Mulholland the navigator on DX-P:

ʺFlying Officer Alexander Eric Mulholland was born in Ballater, Scotland in June 1914. He was the only son of Alexander Mulholland, jeweller and goldsmith, and Alice Mulholland, who was a cousin of our mother.

Eric, as he was known, went to Robert Gordon's College and then to Aberdeen University. While an undergraduate, he served as a sergeant in the University Officers' Training Corps. After graduating with Honours in French and Spanish he went on to the Aberdeen Teacher Training Centre. While there he privately studied Portuguese. He was the first University graduate in our family.

In December 1939, while schoolmaster at Luthermuir School, he joined the Army, and for eighteen months held a commission in the Royal Scots Fusiliers. He worked in a Censorship Office in Glasgow. He told his cousin, Betty Smith, that he felt he was not doing anything to help the war effort. He volunteered to serve with the Royal Air Force.

On 6 August 1941, Eric married Muriel Crombie Smith, a foreign correspondent. He had a sister, Alice, who died aged 41 in 1948. She had two sons one of whom had three daughters. My sister and I never met Eric so the little we know of his life, is the result of visits to his grieving mother. We used to amuse ourselves looking through his sketch books of black and white drawings. Also, we believe he took part in Students' Shows which are still going strong after ninety years. They were part of Aberdeen University Charities Campaign.

Eric's name is on the memorial wall of King's College Chapel and we are very proud to know that he, along with his crew, will always be remembered on the monument at St. Maria-Lierde and at Geraardsbergen in Belgium.ʺ

Muriel Crombie – Eric Mulholland’s wife. The photo was found in Eric’s locker after the crash.

In 2000 at a memorial event, one of Roden Pickford’s relatives (his daughter’s husband) was shown a watch supposedly belonging to Bowle. But then the trail goes cold until September 2012, an unidentified Belgian gentlemen told a member of the Wings of Memory that he was in possession of the watch.

Unidentified local speaks with Wings of Memory member about the ‘Bowles watch’, September 2012

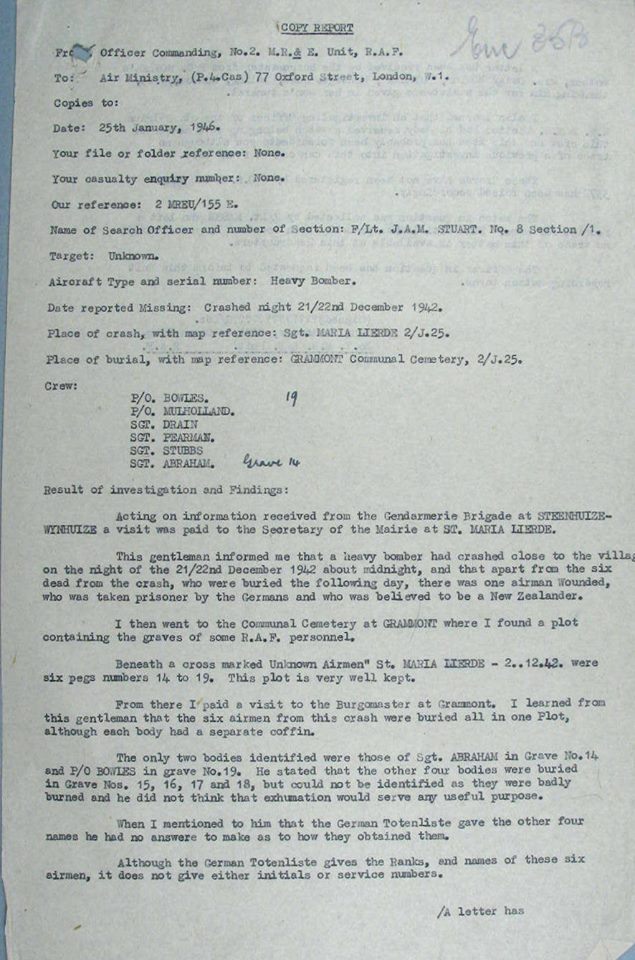

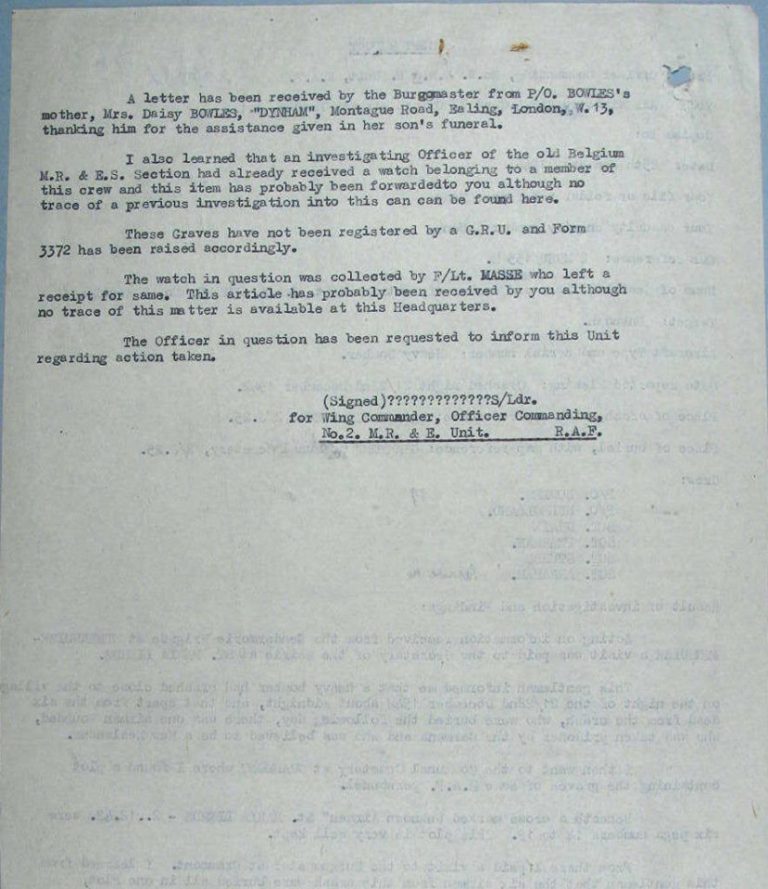

Unable to trace the informant, the trail goes cold once more until March 2014, when information about the watch emerges in in a report tot he Air Ministry dated January 1946. This report, into the whereabouts of the crew of DX-P, notes that the Belgian MR & ES Section had received a watch belonging to one of the crew. It also noted that the watch had been collected by a Flight Lieutenant Masse and probably forwarded to the Air Ministry in London.

In April the following year, during a visit to Lierde by a relative of Eric Mulholland’s widow, further news came to light. Mulholland’s father had been a jeweller specialising in expensive watches and jewellery, and the watch found had not been a regular navigator or pilot watch. It appeared that the watch found in the field in Steenhuyze had been a Cartier. A very similar restored copy of the watch had recently been sold at an auction in the UK.

The Cartier watch sold at auction in the UK

Could this have been the watch found in 1942? Could it have belonged to Eric Mulholland? The owner of the watch was not willing to allow further examination and so the mystery of the watch continues.

In March 2014, Dirk de Quick was contacted by a man who was 4 years old when DX-P came down in Lierde. His father had reportedly taken a parachute from the crash site and made a coat with it. While there was no proof where the parachute had come from, the family had lived in Steenhuyze where Pickford had landed. The coat had been forgotten for many years until found along with a lot of other artefacts related to the War.

Dirk de Quick (right) seen examining the coat

Dirk reported that under the arms of the coat the fabric had a lighter colour and felt like a parachute. The inside of the coat was much darker and not a lining. Could it have been made from the parachute of one of DX-P’s crew? The mystery remained unanswered.

On 26 October 2014, the community of Lierde complete the relocation of the memorial to the crew of DX-P (still in the centre of the village). The steady flow of relatives of the crew continues with another from Australian friends.

Allan Smith from New Zealand, a relative of Eric Mulholland, together with members of Wings of Memory at the new memorial site in Lierde, October 2014

Allan Smith pays his respects to the crew of DX-P at the Geraardsbergen cemetery

Allan Smith and Wings of Memory members discuss the latest developments

Visit to Lierde by Graham and Faye Brown, June 2015. Graham was cousin of Australian Sergeant Cecil Stubbs (Flight engineer on DX-P)

In February 2017, Padre Walter Peeters, Honorary Chaplain to the Belgian RAFA passed away. Aged 85, Padre Peeters is seen here during the 10th anniversary commemoration of the unveiling of the DX-P memorial in 2012.

No matter what the weather, the community of Lierde and members of Wings of Memory never fail to commemorate the loss of DX-P, to the minute, each year on 21 December.