57 Squadron - 1939-1945 - World War II

Operating the Blenheim from its base in France at the outbreak of World War II, 57 Squadron switched from reconnaissance to bombing operations with the German advance into the Low Countries in May 1940. The squadron was forced to retreat in France before returning to England in May 1940. From Wyton, the Squadron moved to Scoland and from July to October 1940 conducted anti-shipping sweeps over the North Sea. Having moved south again to RAF Feltwell and re-equipped with the Wellington, from January 1941 the Squadron joined the strategic night-bombing offensive. In September 1942, the Squadron moved to RAF Scampton and converted to the Lancaster. From August 1943 until the end of the War, the Squadron flew from RAF East Kirkby, Lincolnshire.

The Squadron served in three different groups but always suffered higher-than-average casualties. Its percentage loss rate was the highest while in 2 Group, the highest of the Wellington squadrons on 3 Group, and the highest for all aircraft types combined, within Bomber Command

Flight Sergeant Thomas James Lightfoot

Association Member Mark Taylor, has pieced together various pieces of information relating to the service of his great uncle, Flight Sergeant Thomas James (Jim) Lightfoot (1485692) who flew as a navigator with 57 Squadron from East Kirkby. Jim’s crew was shot down on 24 February 1944 and along with Sergeant Francis Butler (1359064) lost his life, while the other crew members were taken POW – with the exception of Sergeant Greenwell who evaded; his photo is in the museum at East Kirkby.

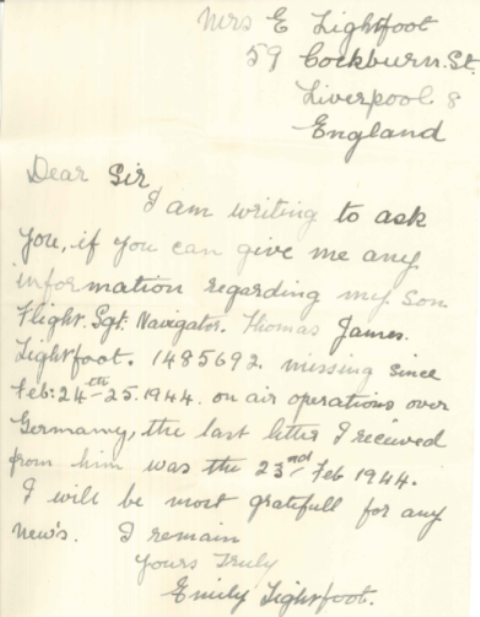

Mark has unearthed two very moving letters about the crash. The first was sent in April/early May 1945 by Emily, Jim Lightfoot’s mother (and Mark’s great grandmother) desperate for news of her son Jim, to the aircraft captain, Flying Officer Norman Harland.

Dear Sir,

I am writing to ask you, if you can give me any information regarding my son Flight Sgt Navigator Thomas James Lightfoot. 1485692 missing since February 24-25th 1944 on air operations over Germany, the last letter I received from him was 23 February 1944.

I will be most grateful for any news.

I remain

yours truly

Emily Lightfoot

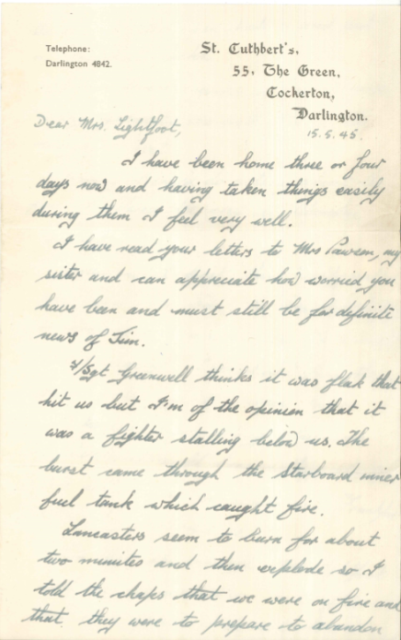

Norman’s reply is dated 19 May 1945 and tells the harrowing tale of the engagement of the Lancaster with the Germans, the subsequent fire and order to abandon the aircraft.

Dear Mrs Lightfoot,

I have been home for three or four days now and having taken things easily during them I feel very well.

I have read your letters to Mrs Lawson, my sister and can appreciate how worried you have been and must still be for definite news of Jim.

Flight Sgt Greenwell thinks it was flak that hit us but I'm of the opinion that it was a fighter stalling below us. The first came through the starboard inner fuel tank which caught fire.

Lancaster's seem to burn for about two minutes and then explode so I told the chaps that we were on fire and that they were to prepare to abandon the aircraft; that is open hatches and put on parachute packs.

Gordon Levers, engineer was in the nose, Freddie Greenwell was with Jim on the navigator's seat.

Finding I could do nothing about the fire I ordered the crew to “abandon” aircraft.

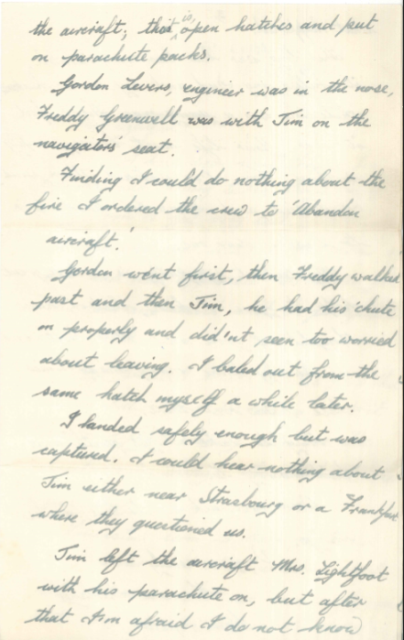

Gordon went first then Freddie walked past and then Jim, he had his ‘chute on properly and didn't seem too worried about leaving. I baled out from the same hatch myself a while later.

I landed safely enough but was captured. I could hear nothing about Jim either near Strasbourg or at Frankfurt where they questioned us.

Jim left the aircraft Mrs Lightfoot with his parachute on but after that I'm afraid I do not know what happened.

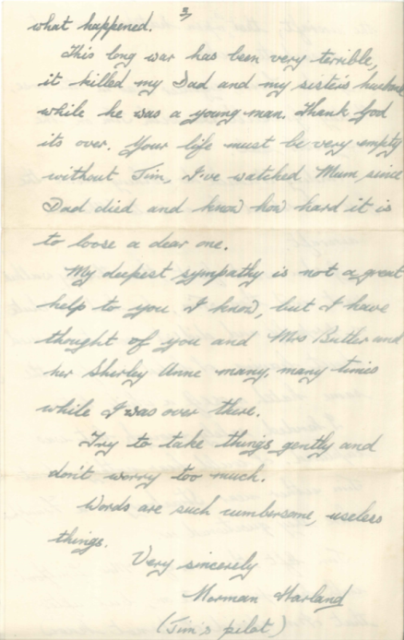

This long war has been very terrible, it killed my dad and my sister’s husband while he was a young man. Thank God it's over. Your life must be very empty without Jim, I've watched mum since dad died and know how hard it is to lose a dear one.

My deepest sympathy is not a great help to you I know but I have thought of you and Mrs Butler and her ShirleyAnne many, many times whilst I was over there.

Try to take things gently and don't worry too much.

Words are such cumbersome useless things.

Very sincerely

Norman Harland (Jim’s pilot)

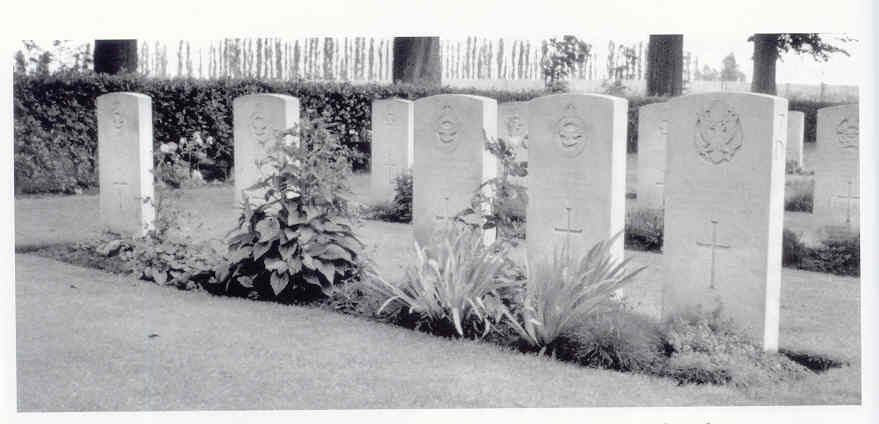

Emily Lightfoot laying flowers at crew members graves near Strasbourg - 1961

3-4-November 1943 Lancaster I W4822 DX-P

On the night of 3/4 November 1943, a large force comprising 589 aircraft were tasked to bomb targets around Dusseldorf. 57 Squadron’s DX-P piloted by 1st Lieutenant Don West took off from RAF East Kirkby at 1722 hours. It was attacked by an unknown German fighter while outbound to the target near Monchengladbach and subsequently crashed at Hechtel-Eksel, Belgium.

1Lt Don West USAAF Pilot

Fg Off Robert Clements RCAF 2nd Pilot (Evaded capture)

Sgt William Neil Flight Engineer

Plt Off Norman Buggy Navigator (Taken POW)

Fg Off James McP Elliott Bomb Aimer (Evaded capture)

Sgt Harry McKernin Wireless Operator

Sgt Francis Heaton Upper Gunner

Sgt John Edmunds Rear Gunner

Three crew members managed to bale out. Fg Off Robert Clements RCAF (only along for a familiarisation flight). Fg Off James McP Elliott managed to evade capture. While Plt Off Norman Buggy the navigator was taken POW. The crew members that were killed in the crash are buried in Heverlee cemetery. The raid also marked the first large scale test of the G-H blind bombing device used by 38 Lancaster MkII aircraft from 3 and 6 Groups, against the Mannesmann tubular steel works.

Jimmy Elliot and Robert Clements

Graves of McKernin, Neil and West at Heverlee, Belgium

8/9 July 1943 Lancaster Mk III ED947 DX-G

Back row: Hodgson, Walker. Front row: Bailey, Lewis and Twigg.

Targeting Köln, as part of a 653 aircraft raid, DX-G of 57 Squadron took off from RAF Scampton at 2216 on 8 July 1943. Unconfirmed reports suggest that the aircraft was shot down by a pilot of the Luftwaffe’s 12/NJG4 and it crashed at Evergem. Moments before the crash, the crew baled out having managed to jettison the bomb load which fell on the village of Oosteeklo at around 0038 hours. All of the crew were taken POW by the Germans.

Sgt Hilary Lewis Pilot (Taken POW)

Sgt John Seeles Flight Engineer (Taken POW)

Sgt John Twigg Navigator (Taken POW)

Sgt William Bailey Bomb Aimer (Taken POW)

Sgt Joseph Hodgson Wireless Operator (Taken POW)

Sgt James Stevenson Upper Gunner (Taken POW)

Sgt Howard Dewar RCAF Rear Gunner (Taken POW)

Sgt Dewar replaced wounded Sgt ‘Johnny’ Walker as the Rear Gunner for this operation. Sgt Walker, Flight Engineer Sgt Seeles and Upper Gunner Sgt Stevenson are missing from the photo, and are assumed to have joined the rest of the crew when they arrived on 57 Squadron

22-23 November 1942 Lancaster I W4360 DX- ?

Sgt Frederick Jones pictured with his wife

A relatively small force (for the day) of 222 aircraft targeted the city of Stuttgart on 22/23 November 1942. Lancaster I W4360 of 57 Squadron took off from RAF Scampton at 1839 hours. However, it was intercepted and shot down on its way home by a German nighfighter flown by Oberltnt Ludwig Meister of I/NJG4. The aircraft crashed at 2348 between Maleves and Tourinnes-St-Lambert, Brabant, Belgium. All crew members died and are buried at the cemetery of Heverlee.

Sgt Jack Ashton Pilot

Sgt Alfred Stansfield Flight Engineer

Sgt Alan Mckinlay Navigator

Sgt Leonard Webber Bomb Aimer

Sgt Frederick Jones Wireless Operator

Sgt Clyde Neilson Upper Gunner

Sgt Gordon Chisholm Rear Gunner

24-25 June 1943 Lancaster I ED781 DX-J

Pilot Stanley Fallows

Wreckage of ED781

Sgt Stanley Fallows Pilot

Sgt John Sykes Flight Engineer

Sgt Harry Naiman Navigator

Sgt I.H. Lambdin Bomb Aimer (Taken POW)

Sgt William Day Wireless Operator

Sgt Francis Steer Upper Gunner

Sgt Raymond Simpson Rear Gunner

ED781 (DX-J) a Lancaster I of 57 Squadron, took off at 2252 from RAF Scampton on 24 June 1943 for its target Wuppertal in the heart of Germany’s Rhur industrial region but never made it. One of the period’s larger operations, a total of 630 aircraft (215 Lancasters, 171 Halifax, 101 Wellingtons, 98 Stirlings and 9 Mosquitos) flew in the operation and 34 aircraft were lost. DX-J aircraft was intercepted and shot down by a German nightfighter from Stab/II/NJG1 flown by Oberltnt Wilhelm Telge. The aircraft crashed at 0120 near Lantin, 8km from the centre of Liege in Belgium. Only Sgt Lambdin, the Bomb Aimer, managed to bale out and was taken POW; the rest of the crew are buried at the cemetery of Heverlee.

57 Squadron at East Kirkby – 12 April 1944

This photo of 57 Squadron’s aircrew was taken on 12 April 1944, at East Kirkby to mark the departure of Wing Commander H W F Fisher DFC. To the left and right of the Boss sit Squadron Leaders P M Wigg DFC and M I Boyle DFC the two Flight Commanders. Within two weeks of the photo being taken, both were dead. Wigg and his crew were killed when they were shot down on 21 April. Boyle and his crew were lost when their aircraft collided mid-air with a 44 Squadron Lancaster on the night of 26/27 April.

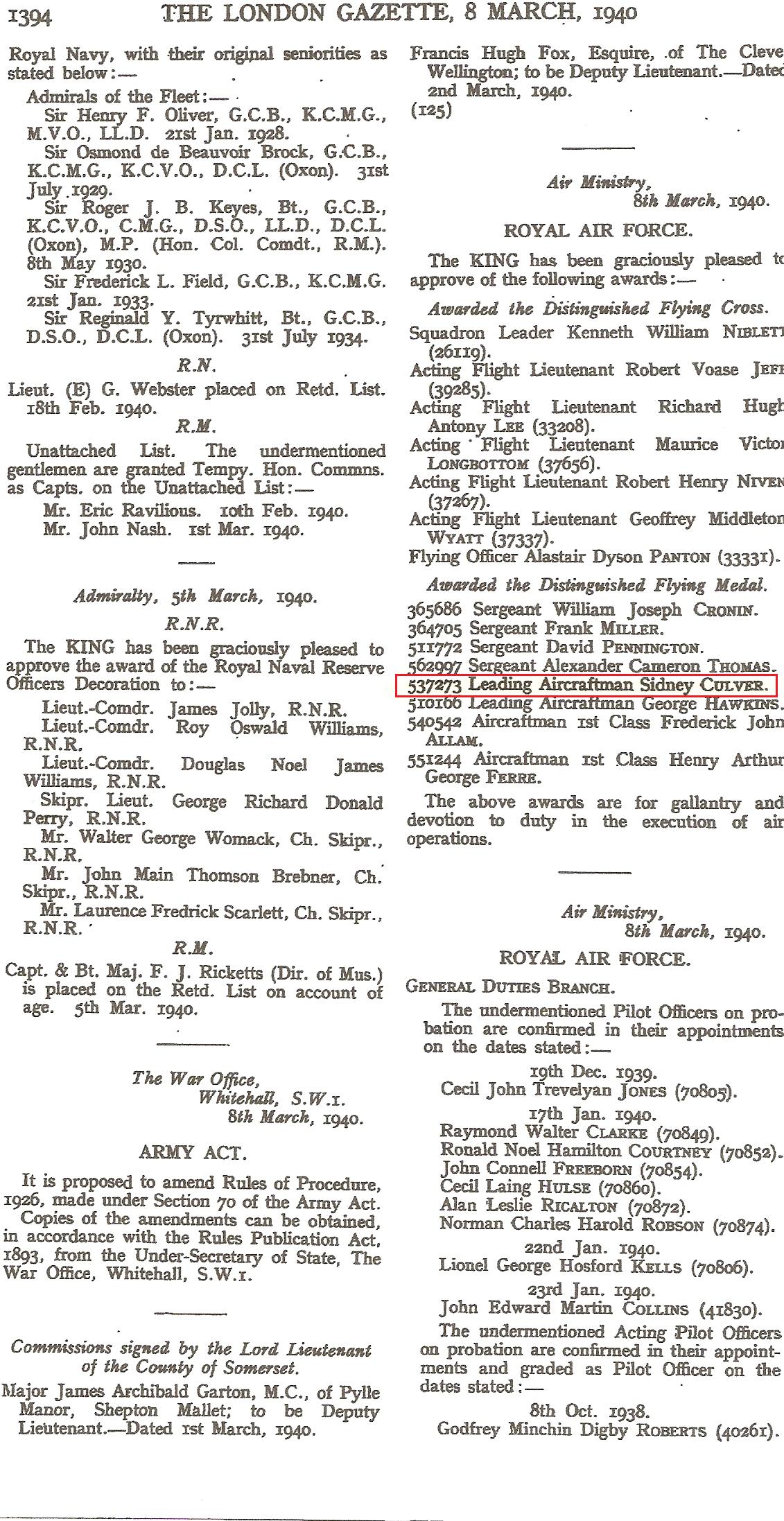

It Wasn't Only Aircrew that Flew – Sid Culver's Story

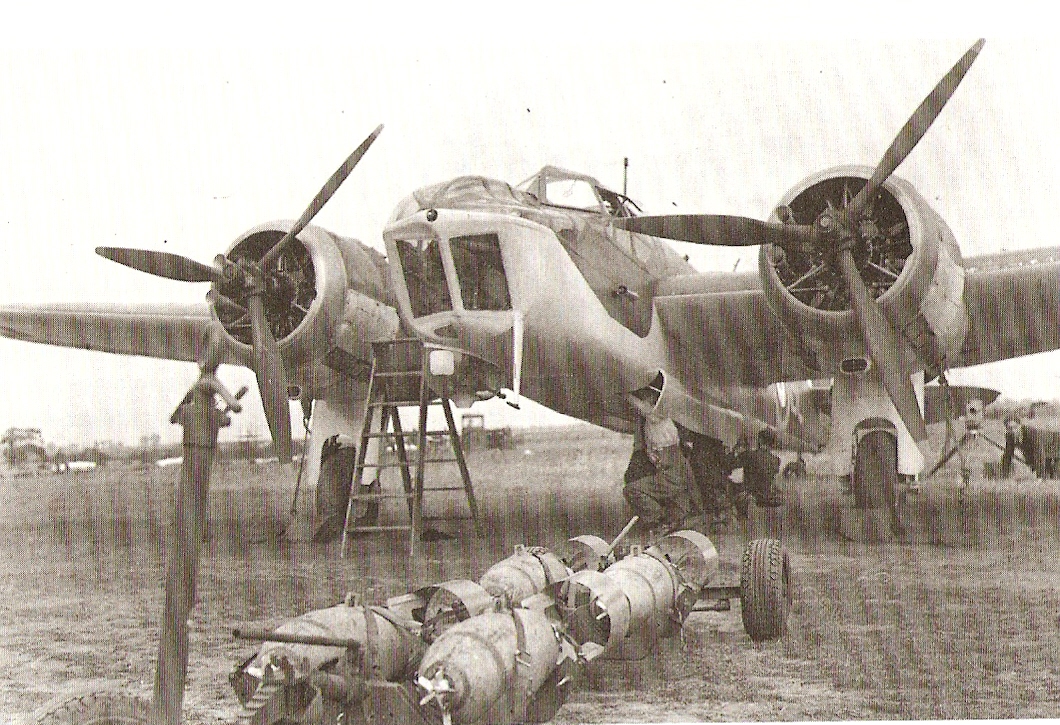

Blenheim MkIV of 57 Sqn

The demand for aircrew at various stages during the War meant that some groundcrew, flew on operational missions, manning one of the gun positions and undertaking other roles. Leading Aircraftman Sid Culver, a 57 Squadron armourer, is recorded as flying as a wireless operator/gunner on Bristol Blenheim Mk IV’s at the outbreak of the War. In March 1940, the Squadron’s first gallantry awards were presented, including the Distinguished Flying Medal to Corporal Sid Culver. The citation for the award records that Sid was

“… the first member to carry out a second reconnaissance over Germany. Both flights involving fighting in the very cold weather for very long distances. His conduct and ability during these flights had a good effect on the aircraft crews at a time when the Squadron suffered losses.”

Sid stayed with 57 Squadron as it re-equipped with Wellingtons and was never far from the action and formally qualified as a wireless operator. Sid managed to escape with his life when his aircraft was forced to crash at East Wratham in March 1941, returning from a raid on Cologne. The following month, his aircraft was forced to ditch off Gibraltar while on a ferry flight from St Eval, after a navigational error led to the aircraft running out of fuel. Sid lost his logbook in the process!

Sid continued to fly throughout the War, following 57 Squadron with a Polish Squadron and also with 7 Squadron Pathfinders. He died, aged 94 in November 2010.

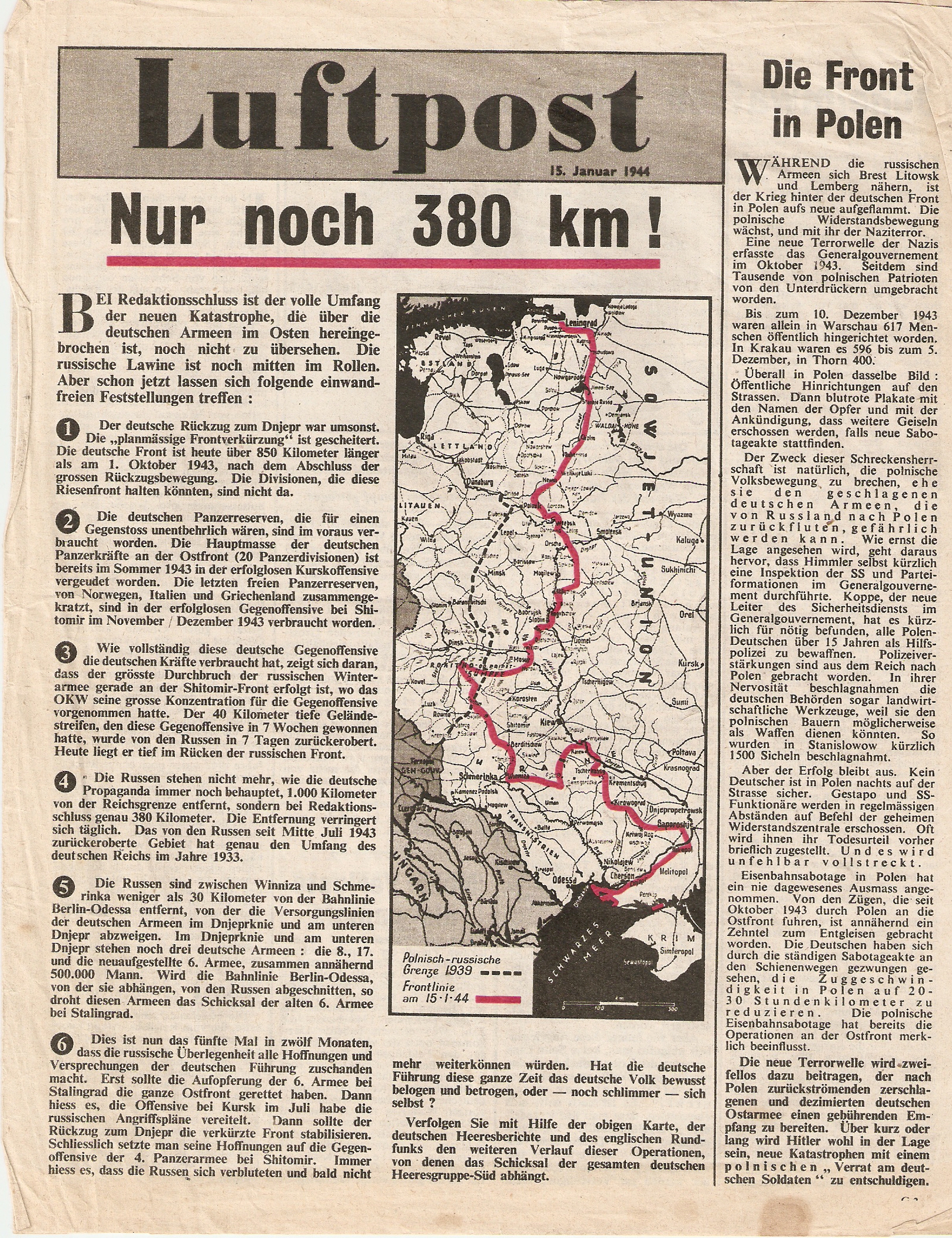

The Propaganda War – Early 1944

As D Day approached, the propaganda war intensified in an attempt to break the will of the German people and convince them of their hopeless position. The ‘Luftpost’ was dropped on Berlin on the night of 30/31 January 1944, describing the rapid advance of Russian troops on the Eastern Front. The same night, forged German food coupons were issued to four 57 Squadron crews in bundles to be dropped over Berlin. The coupons, for use on 6 February, were for cheese (green), meat (blue) and bread (red). Crews were given strict instructions not to drop the bundles unless a positive visual identification of the target was possible.

Efforts to discredit the German Navy and its U Boat Force involved dropping the red booklet titled “The U Boats do not travel far” on Ausburg (around 800 miles from the North Atlantic!) on 25 February 1944. Berliners were warned of more bombing raids and ‘Totaler Krieg Heute’ – “Total War Today” – on 24 March 1944.

Searching for Uncle Jim

As this story from Association Member Nicola Gaughan shows, the hunt for information about past events can be a long and tortuous path.

From an early age I had known about my Uncle Jim, one of my father’s six brothers, whose aircraft had gone missing during World War 2. Apparently, the youngest ever Pilot Officer flying the Wellington, Uncle Jim had also possibly been a navigator. I knew that the family had been devastated by his loss, particularly my Grandmother, who for years hoped he would one day return. Sometimes I heard stories of other WWII planes being found together with the remains of the pilot and I would think to myself “wouldn’t it be nice if they found Uncle Jim one day”.

Over the years, the brothers (my uncles) died until just two were left after my father died in 2006. Eventually there was just Uncle Pat and his health was fast deteriorating. At this stage the thought came to me that perhaps I could find Uncle Jim’s plane myself and tell his last brother what had happened, before he too passed away. I was daunted by the task. How on earth could I find a plane lost over 70 years ago, when the RAF hadn’t been able to? Where and how should I start?

After just a couple of hours on the internet, I had found details of the raid, the weather, and the names of the five crewmembers that had died with Uncle Jim. It had never occurred to me that other people were involved and it suddenly brought things home – five other families probably didn’t know what had happened to their loved ones. So I decided that I had to continue the search and to share any information I discovered with the families of the other crew members.

So the internet search continued and I discovered various war forums, and through one in particular, ww2talk.com, I got lots of guidance, information and encouragement. After creating a forum thread I was able to post information as I went along: to help me keep a record, to ensure important discoveries weren’t lost if I had a computer failure at home, and to share the information.

This forum led me to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) website and I was able to locate personal and family details for all of the crew, except one (more of that later). I also discovered how to retrieve Uncle Jim’s service record, and after a very frustrating 3 month wait, I finally received photocopies of Sgt James Edward Linehan’s service records. It was fascinating to try and decipher the various entries, and with the help of the Department of Research & Information Services at RAF Hendon, I learnt that my uncle had joined the Volunteer Reserve in July 1940, progressed through various flying schools and gained his wings in April 1941.

He then joined 52 OTU to fly Spitfires however, according to my family, after crashing a couple of Spitfires, he was transferred to Bomber Command and joined 11 OTU in July 1941, then joined 57 Squadron on 6 November 1941 whilst they were based at RAF Feltwell. Uncle Jim became a Sergeant in December 1941 and was promoted to Flight Sergeant in February 1942.

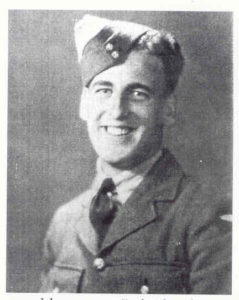

James Edward Linehan

(Photo: Patrick Linehan and the Linehan family)

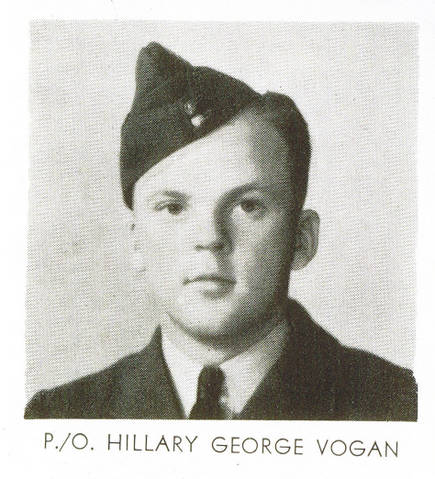

From the National Archives at Kew I discovered that he had flown Wellington Mk1s, Mk2s and Mk3s, and that he was lost on his 12th mission - a raid on Hamburg. He had flown as 2nd pilot and with two different crews, and there were further details of the targets and bomb loads for all the raids and the ‘trades’ of the other crewmen: Plt Off Noel Percy Morse RNZAF (Pilot), Flight Sergeant George Hillary Vogan RNZAF (Observer), Sergeant Graham Lakeman (W/T 1), Sergeant Norman Joseph Naylor (W/T 2) and the Rear Gunner, Sergeant Ronald Richards.

It was a great feeling to learn more about the other crew members, but the information on the CWGC website was pretty patchy, with Morse’s family details being the most complete and Richards’ being non-existent; I started with Morse.

Noel “Bill” Morse

(Photo: Russell Wenholz and the Morse family)

His father was Percy Algernon Morse and with a name like that it didn’t take too long to find his obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald from 1946. My search for more information continued with the Herald, a variety of genealogy web forums, and I checked the Australian White Pages, even telephoning a couple of Morse families until I realised this might be a bit too much.

Hillary Vogan

(Photo: Dawn Prattley and the Vogan family)

The internet didn’t help much with Vogan; I posted a request for information on Cousinconnect.com, and also a Facebook message to a friend in New Zealand asking if she could help via her network. From friends on ww2talk.com I got the NZ white pages which listed several Vogans, including two from Vogan’s home area. Then I got an email via Cousinconnect.com from a distant Vogan cousin, who passed my request to nearer family and I finally received an email from the granddaughter of Vogan’s father’s younger brother, and who was able to give me more detailed information as well as a photo of him.

The previous month I had received a fantastic Christmas present - a response from Australia via the Sydney Morning Herald from Russell Wenholz, who was one of Noel Morse’s nephews. We shared the information we had, including letters from Percy Morse to the RNZAF and others. Russell and his family were extremely grateful, and sent me information and some pictures of Morse, who preferred to be known as Bill.

Having traced the Antipodean families, I turned my attentions to the UK crew members, starting with Sgt Graham Lakeman. According to the CWGC, he had been born in Plymouth and had been an only child. I thought I might not find any living family, but then I found his family in the 1901 census and discovered Lakeman’s father Sidney Harold was one of 8 children - surely I would find someone.

I contacted the local newspapers and was interviewed on air by BBC Plymouth, but to no avail. Then, within some of my father’s paperwork, I found a letter from Lakeman’s father to my grandfather - Uncle Jim’s father - asking if they had heard any news. It was addressed from Greenock in Scotland. Wondering if the family had been bombed out during the Plymouth bombing and moved north to stay with friends or family, I contacted the Greenock Times and they ran an article for me, but again no luck. In desperation I started to ring Lakemans whose numbers I found on the Internet, but always it was the same thing - they weren’t the right family.

Just as I thought my enquiries were running cold, I was contacted by Ken Lakeman’s son Terry Lakeman, a keen genealogist and researcher. Terry didn’t know anything about Graham, however, quite by chance, Terry was told of a surviving relative of Harold Sidney Lakeman, brother of Sgt Lakeman’s father Sidney Harold Lakeman. Reta Riddler, a lady of 88, was the last child of Harold; Terry decided to visit her and to tell her of my search.

Graham Lakeman

(Photo: Reta Riddler and Terry Lakeman)

The following week I met both Terry and Reta. We spent two emotional hours with her, talking about Graham, telling her about my search, what I’d found out, and I showed her the original letter from Sidney Lakeman to my Grandfather. It was such an incredible afternoon and I felt so pleased to have been able to bring her such comfort, as she had been about 17 when he went missing and remembered how distraught their family had been. She kindly allowed me to photograph a photo of Graham that she had in an album.

Now it was a case of three down, two to go. These last two proved a little more difficult, but once again fate, luck, synchronicity, whatever you want to call it came to my aid.

I had made contact with Douwe Drijver, Treasurer and researcher at the Stichting Missing Airmen Memorial Foundation in Leeuwarden, Holland. The Foundation searches for crash sites of planes lost in Friesland and traces families of the crewmen lost or injured. In the summer of 2011, I was invited attend a Memorial Ceremony for a crew they had traced. They held a small reception for the families which were interviewed by the Friesian press and a Daily Express reporter.

Douwe and the Foundation obtained various records to help with my search, including Sidney Lakeman’s death certificate and the service records of Sgts Naylor and Richards. From these, I was able to discover that Sgt Norman Joseph Naylor had been born in Dunfermline and I was then able to obtain his birth certificate. I also got my first solid information about Richards, his date and place of birth, but it soon proved to be more complicated than that.

I contacted various newspapers in the Dunfermline area, but had no luck. Continuing the search for Richards, I asked the guys on ww2talk.com to cross check his details on Ancestry.co.uk, but nothing matched, not marriages, births or anything - all very frustrating.

The Internet is a funny animal. You can draw a blank one day, but another day, using the same search criteria, something can pop up; this was the case with Sgt Naylor. Having scoured Scotland, I found him listed on the Royal British Legion Chipping Norton branch website. I contacted the Branch, local newspapers and the Chipping Norton museum. There, the curator Pauline Watkins was able to confirm that Naylor’s brother, Norman, had been a fireman in the town. Norman’s daughter, Kay had lived in the house but had moved to the USA, although she still kept in touch with the new owners. So we were able to contact Kay and I hope to pursue this contact soon. Meanwhile the Chipping Norton museum was able to find me a photo of Naylor.

Norman Naylor

(Photo: The Chipping Norton Museum c/o Pauline Watkins)

So, to Sgt Ronald Geoffrey Richards - my mystery man. None of the information seemed to make sense, he didn’t exist. Perhaps he was using a false name or had been adopted. My enquiries with various children’s charities and Wakefield institutions led nowhere. Then I got a lead from someone via the ww2talk.com forum who thought he was distantly related. He was able to tell me that not only had Sgt Richards changed his name, but the whole family had changed their name from Cheetham. Now things started to come together; I started to investigate Ronald Cheetham and using the family details from my contact, I discovered that he had been born on 14 May 1923, not 1922 as stated in his service records.

My contact from Rootschat was a distant relative of Richards, and I learnt that Sgt Richards’ father was Horace Cheetham, and his uncles Augustus Alexander and Leslie Alexander Cheetham. Roland had two brothers called Oswald Victor and Sydney Theodore Cheetham. In 1934 they all changed their name by Deed Poll. They were all photographers, including their great grandfather Richard Cheetham, photographer to the Royal Court (later Richard Richards or ‘Dickie twice’)

Jean, my Rootschat contact, was able to put me in contact with Sydney Theodore’s (Roland’s brother) son Jeremy. Three weeks later I got a phone call from a very shocked but happy man, Jeremy Richards, nephew of Sgt Richards. The letter that I had written to him had finally arrived, having done the rounds of Wakefield as the address details had been slightly wrong. Apparently he had just been up to the attic to retrieve the photo of Sgt Richards, which for many years had taken pride of place on the family’s mantelpiece, when my letter dropped through his door.

Douwe and the Foundation obtained various records to help with my search, including Sidney Lakeman’s death certificate and the service records of Sgts Naylor and Richards. From these, I was able to discover that Sgt Norman Joseph Naylor had been born in Dunfermline and I was then able to obtain his birth certificate. I also got my first solid information about Richards, his date and place of birth, but it soon proved to be more complicated than that.

Roland Richards

(Photo: Jeremy Richards and family)

We had a long chat and it seems that Sgt Richards may have signed up under age and not told his family of the details that he gave the RAF. The family had tried to trace his service records but had been looking for Roland Richards born 1923 and the RAF files had him as Ronald Richards born 1922. The family is now looking at having the details on the Runnymede Memorial changed.

I was able to contact all the families and invite them to the dedication of the Bomber Command Memorial on 28 June. Along with members of my family and Jeremy Richards, we attended the ceremony in the blazing London sunshine. Just before the Ceremony, my cousin Jennifer handed me a beautifully carved wooden box and urged me to open it. Inside was a brief note from her mother, my Auntie Joyce, thanking me on behalf of herself and the Linehan brothers for looking for Jim. She also gave me the only thing she still had of his, his RAF service handkerchief, still ironed and folded neatly, wrapped carefully in tissue paper. I was in bits, but very honoured.

Uncle Jim never had a funeral or a memorial service as the family had always hoped he would come home. The Unveiling Ceremony proved to be a very fitting Memorial Service for him. It’s not every day that Her Majesty the Queen comes to your funeral.

The Bomber Command Memorial, Green Park, London

(Photos: Nicola Gaughan)

I’ve found the search to be very interesting, frustrating, exciting and unexpectedly emotional. On many occasions I’ve been brought to tears. Each snippet of information has added more to the story leading me onwards to the next connection. I’m proud of what I’ve achieved and what I’ve been able to do for the crew and their families; the closure of sorts that I’ve been able to bring to families still grieving for their loved ones. I’m also immensely proud of what my uncle and his crew, and many thousands like them did for us.

I am continuing the search for the plane itself and hopefully one day I will be able to write about its recovery and the repatriation of any remains.