57 Squadron - 1959-1986 - V Force

57 Squadron re-formed again on 1 January 1959 at RAF Honington, flying the Victor B Mk1 and B Mk 1A as part of the airborne nuclear deterrent force. In December 1965 the Squadron moved once more, to RAF Marham, and converted to the air-to-air refueling role. RAF Marham was to remain the home of 57 Squadron for the next 21 years until is disbandment once again in June 1986.

The East Kirkby Memorial

The formation of 57 & 630 Squadron’s Association was first discussed at a meeting of interested parties in 1977 at RAF Scampton, and agreement was reached to meet again the following year at East Kirkby. A whip round has held to raise funds for a memorial to be made and erected at the Squadron’s old wartime airfield.

This could not have been achieved without the support and permission of the landowners – the Panton family – who had farmed land near East Kirkby during the War, and subsequently established a thriving business at the old airfield.

On 7 October 1979, the memorial to 57 and 630 Squadrons was dedicated on the former site of the RAF East Kirkby guardroom. The photos above show the memorial, the Order of Service for the dedication ceremony, and the principal wreath layers. These are led by OC 57 Squadron, Wing Commander Roger Betts. He is flanked to the left (as we look) by ‘Shorty’ McLoud RCAF (ex-630 Squadron) and Roland Hammersley DFM RAF (ex-57 Squadron).

The Panton family for many years had sought a way in which they could honour the memory of Plt Off Christopher Panton, a Flight Engineer with 433 Squadron. He was killed along with the rest of the crew when his Halifax was shot down nearing Nuremberg on 30 March 1944. Harold and Fred (pictured above) had been school children when their older brother Chris was killed.

When Lancaster NX-611 came up for sale in 1983, the two brothers snatched it up and brought it to the family land at East Kirkby. It subsequently become the centrepiece and main attraction at the Lincolnshire Aviation Heritage Centre at East Kirkby, opened by the Panton family in 1988.

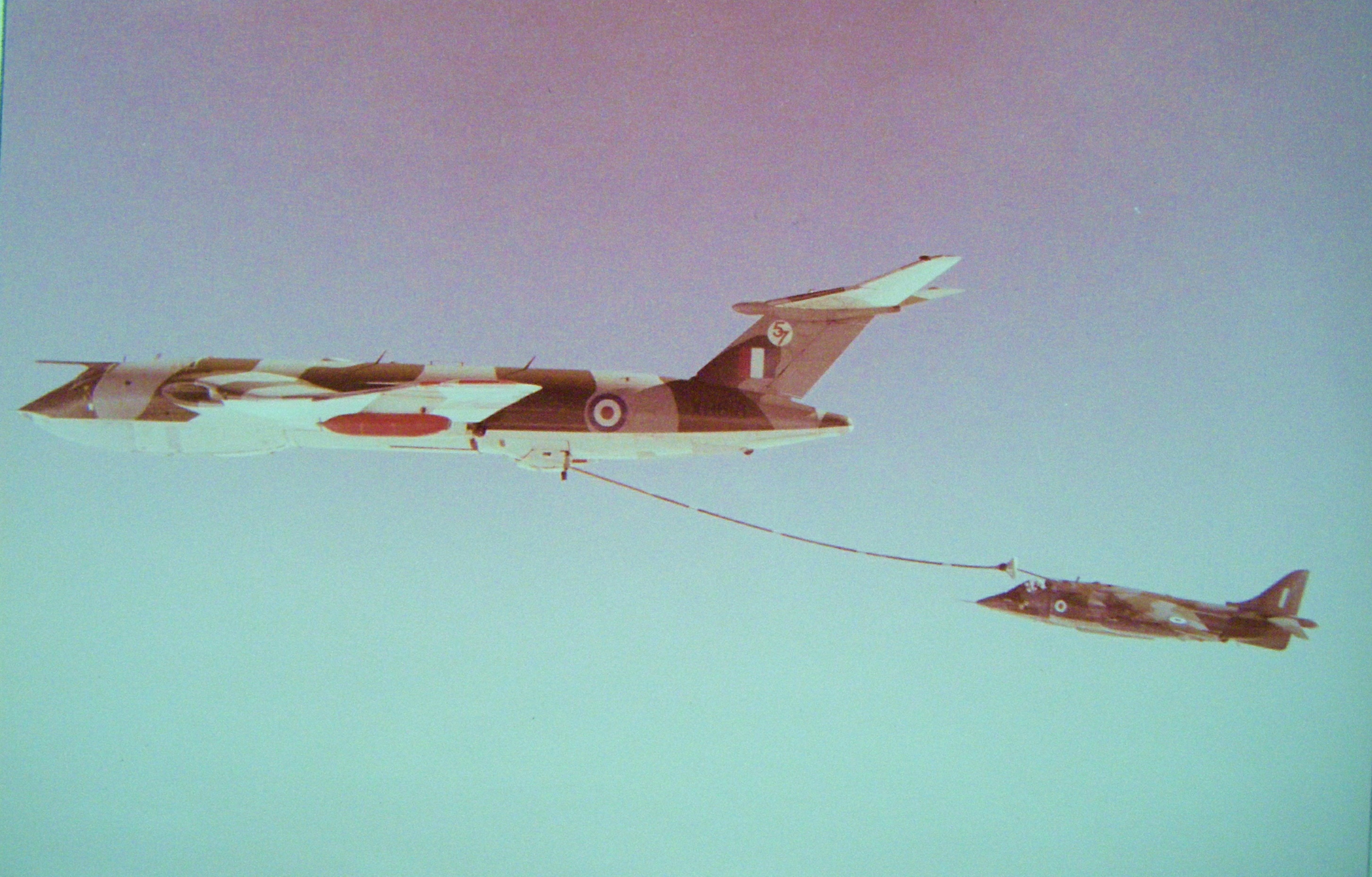

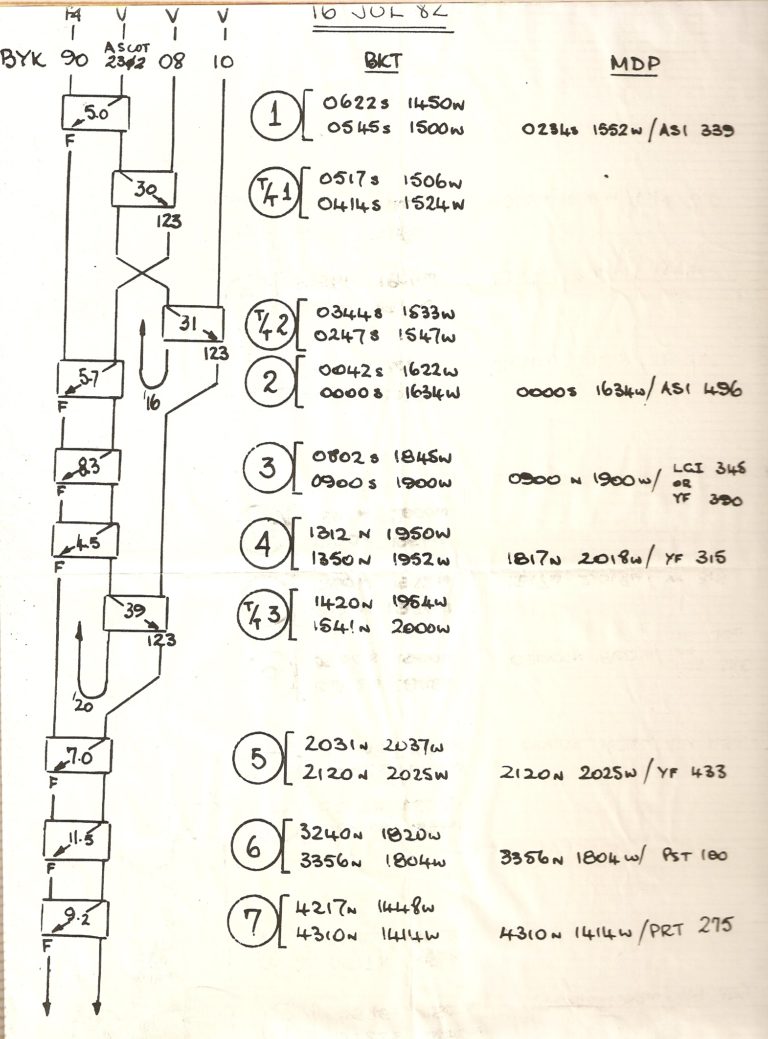

Phantom Return to the UK from Ascension Island – July 1982

The Argentinian surrender on the Falkland Islands on 14 June 1982, signalled the end of the conflict and the start of a complex operation to return military assets to the UK. Included are some of the F-4 Phantom air defence aircraft which had been based in Ascension Island. The refuelling plan above for the non-stop flight from Ascension Island to the UK required three Victor tankers for each Phantom. The Phantom (callsign BYK30) refuels in mid-air seven times. Only one of the Victors (callsign 10) makes it all the way back to the UK in a little over nine hours flying. This Victor receives 70,000 lbs of fuel in flight from the other two Victors, and completes just the final three Phantom refuelling brackets.

57 Squadron Detachment to RAF Leuchars, Scotland for Exercise Elder Forest/Exercise Teamwork – March 1984

57 Squadron Detachment to RAF Leuchars, Scotland for Exercise Elder Forest/Exercise Teamwork – March 1984. RAF Leuchars, near St Andrews, was a frequent and popular detachment base for 57 Squadron throughout the 1980s in support of a variety of air defence and maritime/air exercises.

The Squadron Commander, Wing Commander David Hayward OBE, aircrew and groundcrew of 57 Squadron are pictured on the Quick Reaction Alert pad in front of one of the Squadron’s Victor K2 aircraft.

While the exercises were all designed for national or NATO training, the Soviets often flew around the north of Norway to observe the air activity off the coast of Scotland. Here, a Soviet Tupolev Tu-95 (NATO codename ‘Bear’) is intercepted by an RAF F-4 Phantom, accompanied by a Victor K2 of 57 Squadron.

57 Squadron Disbandment Parade – 30 June 1986

The squadron disbands once more on 30 June 1986 at RAF Marham. The Reviewing Officer is Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham, a former Flight Commander of 57 Squadron. The Victor continued in RAF service with 55 Squadron at RAF Marham until autumn 1993, when it was finally withdrawn from RAF service, bringing to an end the era of the V Force.

57 Squadron Support Bombing Raids on America!

No you are not going mad, 57 Squadron did indeed support a number of bombing raids over America in 1985, but it was all in the interest of competition between the United States Air Force and the RAF.

Just 2 years after its formation in 1946, US Strategic Air Command began holding an annual bombing completion to help improve bombing accuracy. The so-called “SAC Bomb Comp” pitted US bomber squadrons and bases against each other to test the expertise of bomber crews in delivering bombs ‘on target’ and ‘to time’.

The RAF sent its first competitor to the SAC Bomb Comp in 1951 flying the Washington and with the Lincoln the following year. The Vulcan and Valiant made their debut at the Bomb Comp in 1957, and the Vulcan was to become a permanent feature of the competition until just before the 1982 Falklands Conflict.

Vulcan B1 of 101 Sqn at Bergstrom AFB, Texas, 1959

While the USAF included tanker missions and competitions alongside those for the bombers, the RAF didn’t until it was invited to participate with the new Tornado bomber in 1984. That year, 55 Sqn and 617 Sqn, both based at RAF Marham, took part in the SAC Bomb Comp, returning with silverware. The following year, it was the turn of RAF Marham’s other paired units of 27 Sqn and 57 Sqn to compete in what the RAF called Exercise PRAIRIE VORTEX.

There was a keen fight to get on one of the selected crews on both squadrons. Training began in the UK in June and ran through July and most of August, before deployeing to the USA on 27 August. The refuelling ‘trail’ allowed four 57 Sqn Victors to refuel four 27 Sqn Tornados from RAF Marham, via Goose Bay in Canada to Ellsworth Air Force Base in South Dakota.

Led by OC 57 Sqn, Wg Cdr David Heyward, the Victor crews and engineers quickly set up base at Ellsworth and in the nearby Rapid City which was to become our home for the next nine weeks. Training flights were completed through September and until the competition proper began on 8 October.

Victor K2 XL512 of 57 Sqn

While the Tornados were scored on their bombing accuracy, the Victor crews had to navigate to designated rendezvous positions and then drop off the refuelled Tornados at the right place and time. Not everything went to plan. Things became so confused one day, that I managed to navigate such that my aircraft was pointing exactly 180 degrees in the wrong direction at the specified rendezvous time. Fortunately it was not a competition sortie or I might have been on my way home!

27 Sqn Tornado refuelled by a 57 Sqn Victor K2

Each mission required two Victors to fly in close formation just in case there were any refuelling equipment malfunctions. In good weather that was challenging, but in the frequent bad weather it was little short of a miracle. The fully-laden Victors bucking like broncos through thunderstorms and turbulence.

Between the flying there was plenty of time for the crews and engineers to enjoy the delights of South Dakota. Mount Rushmore with its carvings of President’s Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt and Lincoln was just on the doorstep, as was Deadwood home of Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane.

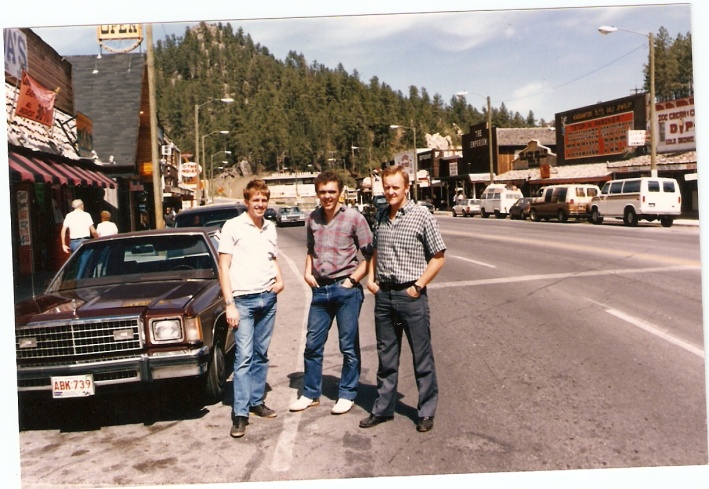

57 Sqn crew visit Deadwood

Nick Barber (Nav Radar), Tony Gunby (Nav Plotter), Fred Harbottle (captain)

Yellowstone National Park was a little further afield, as was the scene of Custer’s Last Stand. Closer to Rapid City were the surreal Badlands wilderness.

The Devil’s Tower (where the alien spaceship lands in the film Close Encounters of the Third Kind) provided too tempting an opportunity for one crew to fly around one day. The subsequent airspace violation from the National Park Authority didn’t result in too much grief – mainly because RAF Marham’s visiting Station Commander was the co-pilot!

The Devil’s Tower, Wyoming

Shopping was a major past-time for everyone, bar-b-q’s, charcoal, cheap jeans and even a toy motor racing set with 57 feet of track. There was also time for sport and for crews to participate in the Rapid City charity bed race.

All good things come to end an end though, and once the final completion sorties had been flown, the crews and engineers suffered a frustrating delay due to bad weather over Canada before completing the homeward refuelling trail on 30/31 October and arriving back to RAF Marham and winter.

So how had the RAF done, specifically the Tornado crews of 27 Sqn? All was revealed 10 days later when a small party from Marham departed the UK by a 10 Sqn VC10 for Barksdale AFB in Louisiana, home of Strategic Air Command. At a ceremony on 12 November the RAF was awarded:

the Curtis E LeMay Bombing Trophy, for B-52/FB-111/Tornado crew with most points in high and low level bombing and time control. RAF Tornado crews were placed 1st and 2nd of 34 crews competing.

the Meyer Trophy – for F/FB-111/Tornado unit with highest Damage Expectancy over 6 missions. The RAF was placed 1st of four units competing.

the Mathis Trophy – 2nd place from 17 units competing for the unit with the most points for high and low level bombing including time control.

Awards Ceremony – Barksdale AFB – 12 November 1985

The highlight of the party that followed the award ceremony occurred when the armed security guard was pushed into the hotel swimming pool for telling us to keep the singing down! The next day, with very sore heads (and fortunately no gunshot wounds), we boarded the VC10 for our return flight to the UK.

The RAF has never competed since in the SAC Bomb Comp. Maybe the RAF decided it could get better value training in other ways, or maybe the USAF was fed up with the Limeys taking away their silver?

I bet they never knew that we celebrated on the VC10 coming home, drinking champagne from the trophies!

A Navigator Plotter on Victor Tankers

After tours on Canberras and Vulcans, and 4 years on the ground, I was posted to 57 Squadron at Marham in 1968. I had visited Marham before but only very briefly. After Air Navigation School in Winnipeg (1952/53) the backlog was such that we soon got out of practice so to keep us air-minded we were sent on familiarisation flight as observers. And that's how a Marham-based Washington (B29) came to feature in my logbook.

RAF Marham – ‘El Adem with grass’

My first visit didn’t auger well for the future. As a healthy bachelor, Marham was not the best place to enjoy an adventurous social life - it was known as "El Adem with grass". Although this clouded my enthusiasm, joining a Tanker Squadron, was for me a new and interesting role which had a tangible meaning not found in the no less important role of nuclear deterrent. Passing fuel to aircraft in flight was perhaps more purposeful than dropping practice bombs into the sea.

As a Navigator/Plotter I attended the Tanker Training Flight (TTF) in October/November 1968. The flying phase comprised of 14 sorties. Although it was primarily the Navigator Radar's responsibility, both navigators were trained to operate refuelling system controls which were located at the Navigator Radar's station, as was a downward facing periscope for monitoring what was going on at the receiving end of the refuelling hoses.

The Navigator Radar Station (note the downward-facing Periscope)

It was a fascinating learning process not least because of the several fail-safe features of the system to prevent mishaps. Fuel could only be passed when a green light indicated a positive connection between tanker and customer. If the link was broken the fuel flow would cut off immediately. Any excess acceleration or deceleration forwards backwards or sideways at the point of contact would have similar consequence. It was a comfortable and comforting system to operate

During this phase we went to RAF Mountbatten for sea survival training. We leapt from a launch clutching our one man dinghy packs which we inflated and scrambled aboard as quickly as possible, stabilising our craft by deploying a small sea anchor. Only the pilot neglected to do this and the fresh breeze had carried him way downwind - the crafty devil had realised that the 'rescue' helicopter would fly into wind to pick us up. He was now the closest to the incoming helicopter and first to enjoy the sanctuary of its cabin. I am told that such cunning represents the difference between pilots and navigators.

The Navigator Radar Station (note the downward-facing Periscope)

Tanker pilots were also trained to take on board fuel from fellow tanker aircraft. This not only gave them the feel of being at the receiving end of transfers but was a necessary procedure for extending the range at which tankers could themselves operate which was so dramatically illustrated in the Black Buck bombing raids on the Falkland Islands in 1982.

Having served on Vulcan as well as Victor Tanker squadrons I can only confirm what an awesome achievement the Black Buck raids were. 57 Squadron's role in those operations should not be understated. Without the ground and air tanker crews' training and experience they just would not have been possible. Flying great distances over open waters the air navigation challenge alone on such missions must have been formidable.

Pilot’s eye view receiving fuel from another Victor I

I think that the Victor Tanker fleet were first fitted out with two refuelling points mounted on the underside of the outer wings. By the time I joined all the Squadron aircraft also had a heavy duty refuelling point in what had been the bomb bay. These were called Hose Drum Units (HDUs).

The centreline Hose Drum Unit (HDU)

The fuel hoses which terminated in a nozzle surrounded by an aerodynamic stabilising drogue. They were retractable by being rewound on to the drum from which they were deployed during flight. Fighter aircraft could use any drogue whilst larger aircraft would use the larger centre drogue only. Refuelling three 'small' aircraft at once was perfectly feasible, but not a standard practice.

The Refuelling Drogue

The Tankers were choc-a bloc with fuel which could be moved around between tanks for transferring and for keeping the Tanker aircraft's centre of gravity within prescribed limits. Synchronising and maintaining airspeeds during fuel transfers was sometimes difficult. For aircraft with a marked difference in speed range from the tanker aircraft, a gentle descent known as 'tobogganing' was sometimes used.

Because we could be deployed anywhere navigational exercises were routinely carried out, with the requirement to practice astro navigation and use limited navigation aids. Throughout Strike Command aircrew had strict training commitments to meet, and we were monitored at intervals by on-board specialist teams know as tactical evaluation teams or "trappers".

Sorties dedicated to refuelling practice would take place in well-defined zones known as tow-lines monitored by ATC services. The tow-lines were identified by their associated fighter station such as Binbrook, Wattisham, Leuchars, Boscombe, and RAF Germany tow-lines. The tanker would fly a trombone pattern while receiver aircraft would practice making contact with the trailed drogues. We would fly up and down these trombones for hours at a time. The navigator operating the refuelling kit was busy all the time but the procedure could get monotonous. But practice for all concerned was absolutely necessary of course.

Victor K1 refuels Lightning

From time to time the non-stop overseas deployment of our fighters would require en route refuelling. Tankers would be prepositioned along the intended route. The stretches of route calculated for optimum fuel transfers would be charted and defined within brackets. The receiving aircraft would aim to start taking on fuel at the start of the bracket, but if the requisite transfer was not complete by the end of the bracket, the receiver would have to divert to a designated en route airfield. The same principals applied to tankers required to take on fuel in flight as part of the plan. And the Tankers had also to ensure that they did not deprive themselves of their own fuel requirements.

Fuel management was always critical. On one occasion we flew to Masirah off the coast of Oman to top up Phantoms travelling non-stop to the Far East. The requirement was such that we had to take off at maximum all up weight with a full fuel load. Unpopular pre-dawn departures were the safest option due to the local ground temperatures.

Victor refuels 2 F-4 Phantoms

On one occasion during pre-flight planning I discovered that HQ Staff had seriously miscalculated the fuel log which fortunately was corrected in good time. I also recall an exercise in the Penang area when we couldn't wind in the central hose. So we headed for a Maritime Danger Area to jettison both it and excess fuel at low level in a fearsome tropical storm. My log book also records just four occasions when we had to RTB (Return To Base), twice for bird strikes and twice for engine problems.

In many ways the refuelling role was perhaps the most mission-oriented role I had experienced. With the sole exception perhaps of two Canberra raids on Egyptian targets during the Suez crisis of 1956. One could get anxious about the fate of aircraft whose refuel needs were critical to their mission even if they were only in peaceful transit. One hoped to get one's own part right by positioning the tanker in the right place at the right time. That was the Navigator Plotter's job.

On occasions we were deployed overseas for a period so provide refuelling support to fighters in unusual environments, using local air to ground firing ranges where possible and air refuelling between mock attacks. Tanker crews were a bit like transport crews meeting each other half way at places such as Cyprus or Gan, some outbound and some inbound. Such Exercises were identified by arbitrary code names such as Piscator, Chicanery, Magic Palm, Blue Nylon, Forthright, High Noon, Ultimacy, Arctic Express, Panther Trail, Bersata Padu, Co-0p.

Gan, Indian Ocean

On occasions we enjoyed task free deployments known as Rangers. A Western Ranger would have Offutt AFB Nebraska as its final destination. Other codeword items in my logbook are Tankex , Phantex, and Litex. I was in the crew which made the first visit to Hong Kong by a Victor Tanker. (10 April 1970). We were greeted by a small reception party and a pretty girl bearing a tray of glasses of beer. Both commodities were appealing

The one episode which perhaps merits special attention is the Daily Mail Air Race of early May 1969. Victor Tankers were used to refuel the Harrier of No 1 Sqn and RN Phantom of 892 Sqn in their dash across the Atlantic. It may have been the first time in which Tankers were used at such extended range across open water. Tanker-to-Tanker fuel transfers were used even more dramatically in the Black Buck raids. Our crew gave the Harrier its first top up just before it reached the Atlantic.